|

| WALSH/LANGAN INTRODUCTION - HOME |

|

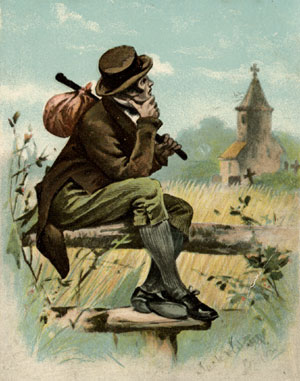

The Emigrant There was simply not enough work in Ireland to pay the rent. Consequently from early times the Irishman and Irishwoman left to find work either seasonally harvesting crops in England or shearing sheep in Scotland or they emigrated on a more permanent basis to England, America, Australia, and New Zealand. The first leg of the journey abroad for most Irish emigrants was on foot. Some only had to walk as far as the nearest town with a train station. Others walked for days to get to a port for the voyage overseas. Most had nothing to carry but the clothes on their backs. |

|

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck

| ||

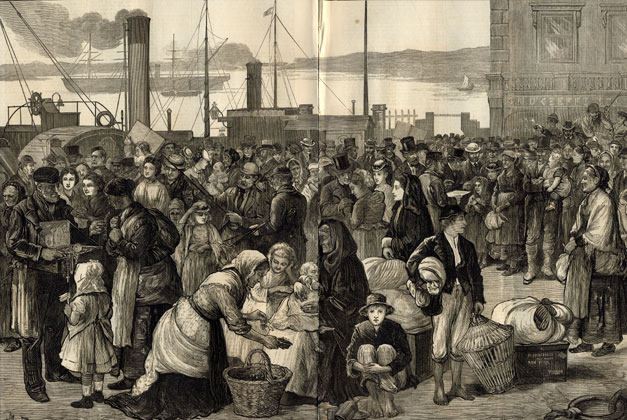

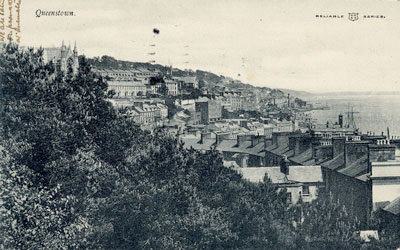

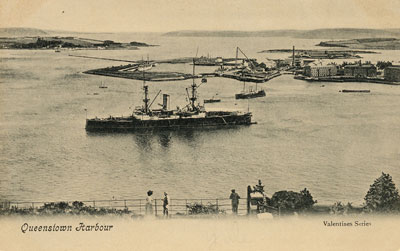

| Queenstown Queenstown was a major port from which the Irish immigrants left Ireland for America. Mathias, Penelope, James and Bridget Langan left from Queenstown in 1892. Joseph and Fanny Walsh left from Queenstown in 1894. |

|

Originally called Cobh (pronounced "cove" ) until Queen Victoria visited in 1849 when the name was changed to Queenstown. It was changed back to Cobh in 1921. Cobh is in Cork Harbor. Between 1848 and 1950 almost six million people left Ireland; two and a half million of them left from Queenstown.

|

|

| IRISH EMIGRANTS LEAVING QUEENSTOWN HARBOUR The Illustrated London News Sept.5, 1874 |

|

Queenstown, Train Station Not posted. Fanny and Joseph Walsh most likely arrived in Queenstown on the train from Ballinrobe. Post card collection of Maggie Land Blanck |

|

Queenstown Postmarked 1906 Post card collection of Maggie Land Blanck |

|

Cobh (Queenstown), Co. Cork |

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

Queenstown at the White Star Wharf |

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

Queenstown Harbour

No postmark Post card collection of Maggie Land Blanck |

| |

| Photo collection of Maggie Land Blanck

| |

| Queenstown Harbour

| |

| |

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck

| |

| Queenstown Harbour

| |

| |

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck

| |

| St. Patrick's Street, Cork, Ireland

Printed on the back: "St Patrick's Street, Cork, Ireland — The capital of the county of Cork in the south of Ireland on the river Lee, 15 miles from the sea. St. Patrick street is one of the main streets. The principle buildings are the Protestant and Roman Catholic Cathedrals and Queen's College" | |

|

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck

|

| Entrance to Queenstown Harbour, ROCHES POINT

|

|

|

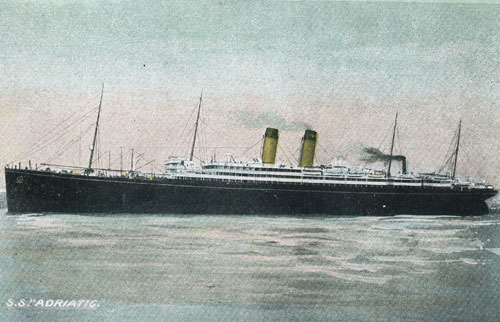

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck The S. S. Adriatic Several of the Walsh/Langan clan listed the Adriatic as the ship on which they come to America. I have never, in fact, found anyone in the Langan/Walsh clan listed on the Adriatic. However, it was typical of several ships that sailed for the White Star Line. There were two ships named the Adriatic that sailed for the White Star Line: One built in 1871 was scrapped in 1898, another Adriatic was built in 1907. This image is of the 1907 ship. Since the Walshes/Langans all immigrated before 1907 if any of them did come on the Adriatic it had to have been on the earlier ship. | |

|

Evening Train for Ballinrobe at Hollymount 1954 |

| The Railway Magazine May 1954, collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

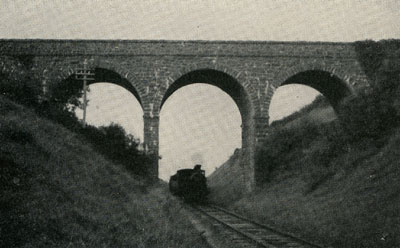

Ballinrobe train passing though the centre span of the Caltra cutting overbridge. |

| The Railway Magazine May 1954, collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

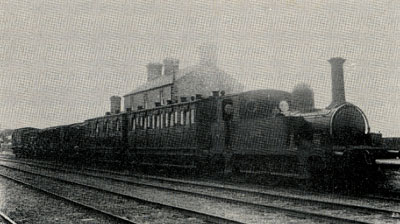

No. 108, Swallow, on a mixed train at Ballinrobe, c. 1905 Notice the passenger cars at the front and the freight cars at the back of the train. |

| The Baronial Lines of the Midland Great Western Railways, Loughrea and Ballinrobe by Padraig O'Cuimin 1972 Transportation Research Associates collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

The branch train, Ballinrobe, c. 1934; loco 559 |

| The Baronial Lines of the Midland Great Western Railways, Loughrea and Ballinrobe by Padraig O'Cuimin 1972 Transportation Research Associates collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

Loco 588 crossing the robe river bridge (T. G. O'Donoghue) |

| The Baronial Lines of the Midland Great Western Railways, Loughrea and Ballinrobe by Padraig O'Cuimin 1972 Transportation Research Associates collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

Hollymount. looking towards Claremorris (T. G. O'Donoghue) |

| The Baronial Lines of the Midland Great Western Railways, Loughrea and Ballinrobe by Padraig O'Cuimin 1972 Transportation Research Associates collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

Ballinrobe, looking towards the end of the line (H. C. Casserley) |

| The Baronial Lines of the Midland Great Western Railways, Loughrea and Ballinrobe by Padraig O'Cuimin 1972 Transportation Research Associates collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

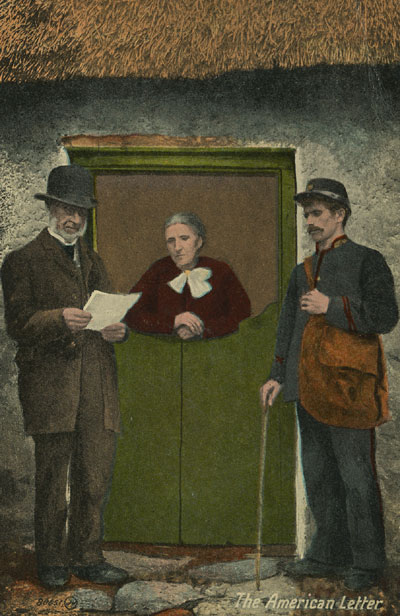

The American Letter The eight-year difference between Michael's immigration and Joseph and Fanny's immigration and the five year span of the Langans immigration, means that there were letters back and forth. One of the important parts of the letters from America was the money that was sent to subsidize the family in Ireland or to pay the fare to send other family members to "Amerikay". Since most Irish peasants born before the mid 1800s were illiterate they had to have someone read the letter to them as illustrated by the following pictures. News from abroad added some excitement to life and letters were shared with neighbors and friends. |

|

| |

|

Printed on the back. A letter from Pat in America There are as many Irish out of Ireland as in it. Two-thirds of the Irish emigrants come to the United States; the others go chiefly to Canada and Australia. The strong ties of family affection, so characteristic of the Celt, were strengthened in Ireland by centuries of poverty and oppression, and intensified at last by famine. The homeward letters do not go empty; a million dollars a year go with them, from brothers and sons, and daughters, and husbands, and lovers, who have found prosperity |

| in far-off Australia or in America, the land of the free. In this letter, we may fancy, Pat telling Nora that he has the cottage nearly finished and that he will send her a ticket to come to him before Christmas. Then Nora will bid her friends and dear old Ireland good-bye as we now do. | |

| Stereo card collection of Maggie Land Blanck. Not dated | |

| |

| Post card collection of

Maggie Land Blanck The American Letter | |

|

|

Print collection of Maggie Land Blanck

Harpers Bazar December 10, 1870

Irish Emigrants Leaving Home Visible on the side of two of the trunks: NEW YORK

This images shows the contrast between the sorrow and the gayety associated with the

"American Wake".

|

|

|

Collection of Maggie Land Blanck The Illustrated London News May 10, 1851 IRISH EMIGRANTS LEAVING HOME- THE PRIEST'S BLESSING |

|

|

|

|

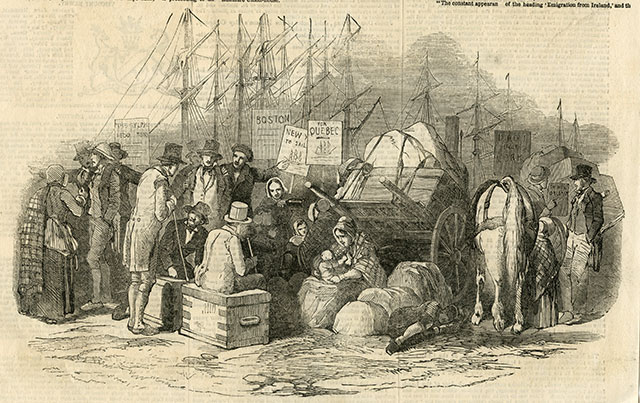

Collection of Maggie Land Blanck,

Illustrated London News May 10, 1851 EMIGRANTS ARRIVAL AT CORK - A SCENE ON THE QUAY |

|

|

| |

| Print collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

| DEPARTURE OF THE IRISH EMIGRANTS AT CLIFTON, COUNTY GALWAY

By A. O. Kelly, The Illustrated London News, July 21, 1883 DEPARTURE OF THE IRISH EMIGRANTS The large Engraving that fills two pages of our Supplement this week is from our Special Artist's drawing of a scene he lately witnessed in the county of Galway. The little town is the capital of Connemara, one of the poorest districts of Ireland. The town is usually dull and the streets empty; but on this occasion the main street was crowded with people from the surrounding district who were about to leave Ireland with a free passage granted by Government under the emigrations clauses of the Arrears Act. There are many similar scenes at present going on throughout the distressed districts of Ireland.Representatives of the Government sought employment in the States for these emigrants although the article does not say where. The emigrants were clothed, had free passage and were given some money "to start with on their arrival at their destination". Thousands apparently availed themselves of the opportunity. The artist "endeavored to introduce some of the types and as much of the character of the scene as he could". The figure in black in the lower left corner is a priest "who people are pressing around, as usual, for advice and assistance" (He's a pretty dandy looking fellow!). Two of the royal Irish constabulary can be seen on the left. The rest are the emigrants taking leave of family and friends and preparing to make their way to the docks to board their ships. Note: Clearly there were multiple routes out of Ireland. I do not know anything about the emigrations out of Galway City.

| |

| |

| Print collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

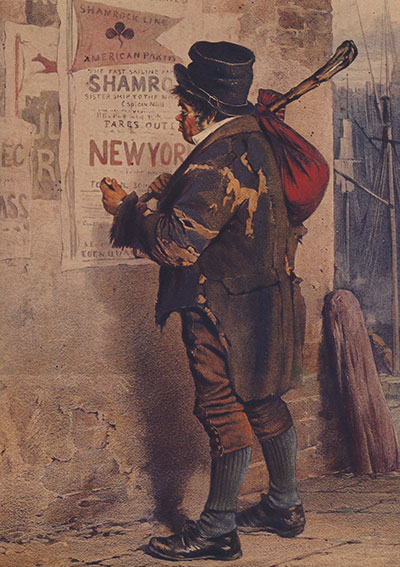

| L'EMIGRATION EN IRELAND- Voir le Bulletin Univers Illustre, No date.

| |

|

|

Collection of Maggie Land Blanck, 2012, publication unknown, date unknown, reprint

|

|

|

|

|

Collection of Maggie Land Blanck May 10, 1851 ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS The emigration agent's office - the passage money paid |

|

|

|

| |

|

Printed on the back. The Exile Even to the casual observer the gradual depopulation of the Emerald Isle had been a most pitiful sight; how, then, it must have affected every true Irish man and every true Irish woman? Never since the Israelite captivity has there been an exodus on such an immense scale. A whole people flying in such numbers that, were the exodus to continue at the same rate, the date would not be far distant when the population would be reduced to a mere handful. In 1841 the population was close on 9 million, whereas at the present day it is no more than half that number. In normal circumstances it should by natural increase have attained to 18 million! There is no doubt, however, that a brighter day is dawning, and that ere long the subject of our illustration will cease to typify an ever present spectre in the lives of the Irish peasantry. |

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land blanck. not dated | |

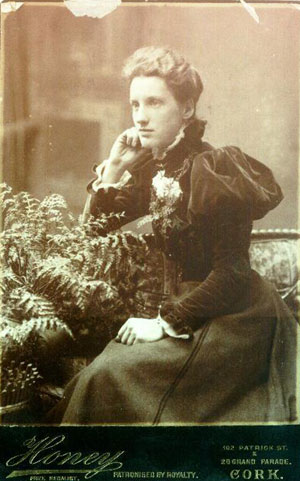

| Maggie Jane Roycroft Emigrated 1887 From Queenstown | |

|

Maggie Jane Roycroft born September 2, 1862 immigrated in 1887 from Queenstown and had her

photograph taken from there "on leaving old Ireland".

She was COI, but also had two letters sent from a Methodist minister, Wm. Clarke, dated 1887, but I am sure her departure and circumstances would have been much the same as the Irish Catholic. She passed on so much of the Irish and Ireland to us grandchildren growing up, and much, much humor; that we are indebted to her forever for her values, wit, and courage. She grew up on a farm at Dunkelly, Goleen on the Mizen Peninsula near Dunmanus; daughter of James Roycroft & Eliza (Connell) Roycroft. She lived in NY for awhile, but her final destination was Chicago, IL. |

| Photo courtesy Jerry Mecier July 2006 | |

|

|

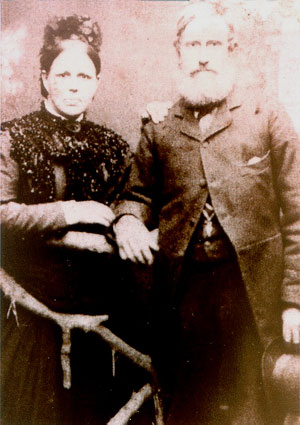

| Photo courtesy Jerry Mecier July 2006 | Maggie's parents, James Roycroft & Eliza (Connell) Roycroft | Maggie's sister Annie at Dunkelly home. |

|

Letters from Ireland By Harriet Martineau, Reinhard S. Speck, 1852 While traveling by public car Harriet Martineau describes some emigrants who joined them near Castlebar: "on approaching a cluster of houses, were were startled — to say the truth, out blood ran cold— at the loud cry of a young girl who ran across the road, with a petticoat over her head, which did not conceal the tears on her convulsed face. A crowd of poor people came from — we know not where — most of the in tears, women weeping quietly, others with unbearable cries. A man, his wife, and three young children were going to America. They were well dressed, all shod, and the little girls bonneted. There was some delay — much delay — about where to put their great box; and the delay was truly painful........ All eyes were fixed on the neighbors who were going away for ever. The last embraces were terrible to see; but worse were the kissings and clasping of hands during the log minutes that remained after the woman and children had taken their seats...... When a distant turn in the road showed the hamlet again, we could just distinguish the people standing where we left them. As for the family, — we could not see the man, who was on the other side of the car. The woman's face was soon like other people's, and the children were eating oatcake very composedly"Martineau commented that the people do not go eagerly, the go "because they must". She had the impression that most people went with little knowledge of what they were going to. They went "because others have gone, because they are sent for, or because the have a general idea that is is a fine thing for them."

| |

| Life in America The fast majority of Irish immigrants, despite the fact that they came from rural area of Ireland, settled in urban areas the United States. Ireland had a long history of immigration with the highest rate of immigration being during the famine years. Joseph Walsh and his siblings and the Langans immigrated during a relatively slow immigration period. Like many Irish newcomers before them the Walshes and Langans were Roman Catholic, relatively poor, and were most likely Gaelic/English speakers with few skills applicable to life in New York City. Upon their arrival in the United States all Irish immigrants were subject to a great deal of prejudice. Signs, which read "No Irish need apply", were common. I have one dated 1915. Classified ads in newspapers pointedly excluded the Irish: for instance "Wanted, a Cook and a Chambermaid. They must be Americans, Scotch, Swiss, or Africans; none others need apply".Even blacks were preferred to the Irish. The Irish immigrant was frequently depicted with ape like features. See the image below for some of the stereotypical portrayals of the Irish immigrant. Though most Irish immigrants came from rural areas of Ireland, they preferred to settle in large cities like Boston and New York. Sociologists believe this is due to the community patterns of rural life and the accessibility of Catholic Churches in the large cities. By the time Joseph Walsh and his siblings and the Langans emigrated in the 1890s the immigrant ships were vastly improved over the "coffin" ships of the mid 1800s. Some steamship companies offered concerts, church services, dances and games on board. According to Kerby A. Miller in "Emigrants and Exiles, Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America, "Usually, an uncle of aunt in the New World financed the initial departure of an eldest son or daughter, who in turn was expected to send prepaid passage tickets and promise further assistance (e.g., a place to live, help in finding employment) to his or her younger brothers and sisters." | |

| |

|

Collection of Maggie Land Blanck 1873 IRISH EMIGRANTS JUST ARRIVED IN NEW YORK | |

|

| |

|

|

Collection of Maggie Land Blanck Harper's Weekly April 4, 1874 REMINISCENCE OF ST. PATRICK'S DAY |

| The Irishman, however, had a much more romantic view of himself | |

| |

| Collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

| In this dreamlike image a young immigrant pines

for his lost love back in Ireland.

| |

| For a list of Ballinrobe residents who immigrated through Ellis Island, New York between 1892 and 1906 go to go to Ballinrobe Immigrants | |

| To see images of the immigrants arrival at the port of New York go to Immigration | |

| If you have any suggestions, corrections, information, copies of documents, or photos that you would like to share with this page, please contact me at maggie@maggieblanck.com |

| JOSEPH WALSH | |||

| MAGGIE LANGAN | |||

| THE LANGANS IN NEW YORK CITY | |||

| LIFE IN IRELAND | |||

| WALSH/LANGAN INTRODUCTION | |||

| HOME | |||

| RETURN TO TOP OF PAGE | |||

|

| |||

| The Temperance Movement For early pictures representing the Temperance Movement in New York City |

|

|

| |

|

Please feel free to link to this web page. You may use images on this web page provided that you give proper acknowledgement to this web page and include the same acknowledgments that I have made to the provenance of the image. Please be judicious. Please don't use all the images. You may quote up to seventy five words of my original text from this web page and use any cited quotes on this web page provided you give proper acknowledgement to this web page and include the same acknowledgments that I have made to the provenance of the information. Please do not cut and paste the whole page. You may NOT make use any of the images or information on this web page for your personal profit. You may NOT claim any content of this web page as your original idea. Thanks, Maggie |

| ©Maggie Land Blanck - Page created 2004 - latest update August 2013 |