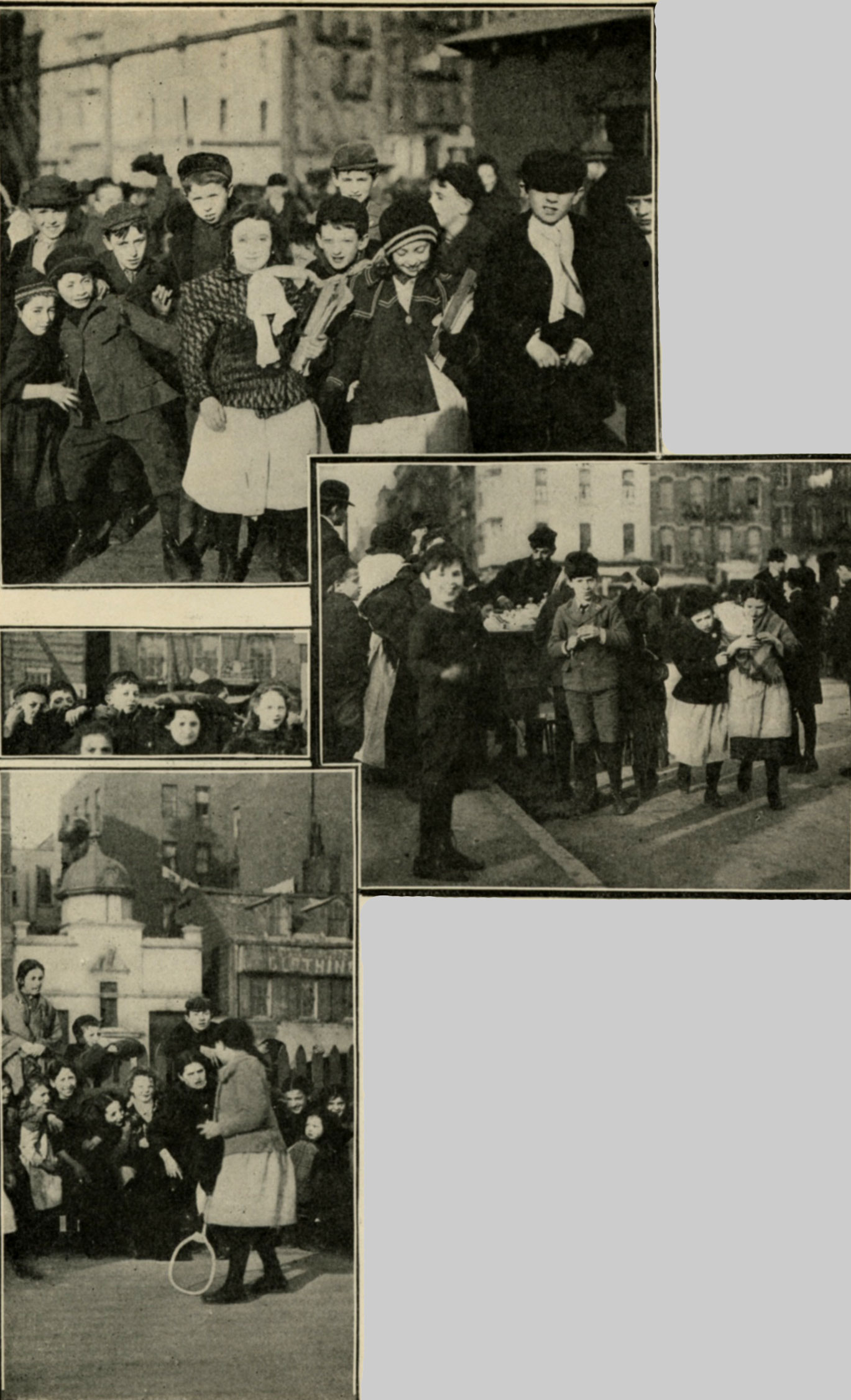

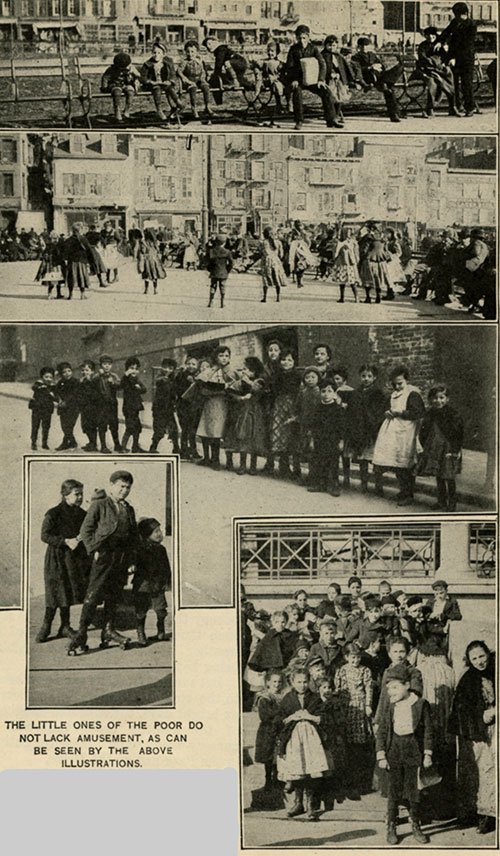

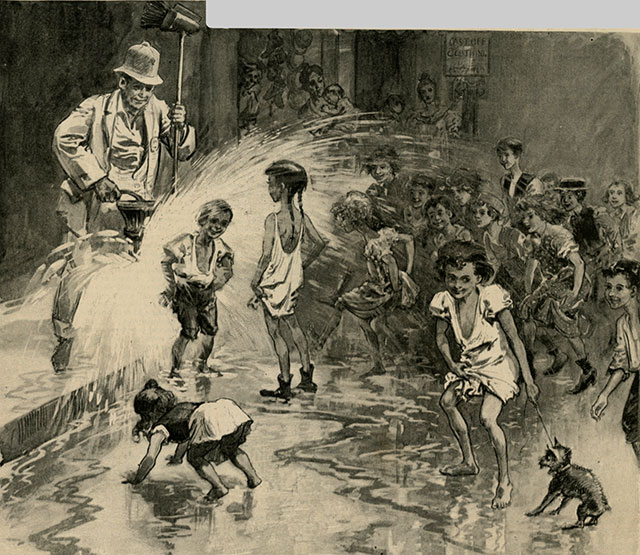

LXVIII. STREET CHILDREN.

In spite of the labors of the Missions and the Reformatory Institutions,

there are ten thousand children living on the streets of New York,

gaining their bread by blacking boots, by selling newspapers, watches,

pins, etc., and by stealing. Some are thrust into the streets by

dissolute parents, some are orphans, some are voluntary outcasts, and

others drift here from the surrounding country. Wherever they may come

from, or however they may get here, they are here, and they are nearly

all leading a vagrant life which will ripen into crime or pauperism.

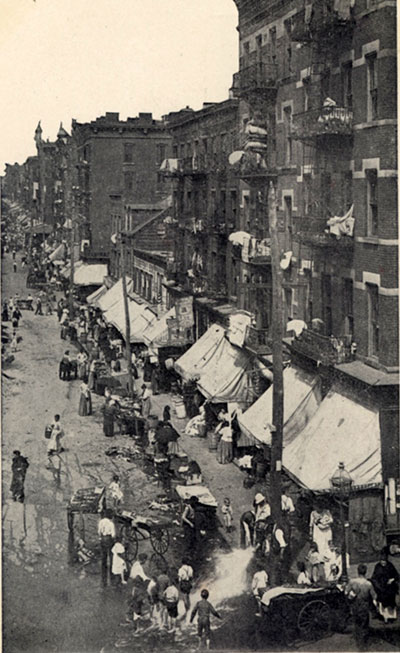

The newsboys constitute an important division of this army of homeless

children. You see them everywhere, in all parts of the city, but they

are most numerous in and about Printing House Square, near the offices of

the great dailies. They rend the air and deafen you with their shrill

cries. They surround you on the sidewalk, and almost force you to buy

their papers. They climb up the steps of the stage, thrust their grim

little faces into the windows, and bring nervous passengers to their feet

with their shrill yells; or, scrambling into a street car, at the risk of

being kicked into the street by a brutal conductor, they will offer you

their papers in such an earnest, appealing way, that, nine times out of

ten, you buy from sheer pity for the child.

The boys who sell the morning papers are very few in number. The

newspaper stands seem to have the whole monopoly of this branch of the

trade, and the efforts of the newsboys are confined to the afternoon

journals--especially the cheap ones--some of which, however, are dear

bargains at a penny. They swarm around the City Hall, and in the eastern

section of the city, below Canal street; and in the former locality, half

a dozen will sometimes surround a luckless pedestrian, thrusting their

wares in his face, and literally forcing him to buy one to get rid of

them. The moment he shows the least disposition to yield, they commence

fighting among themselves for the "honor" of serving him. They are

ragged and dirty. Some have no coats, no shoes, and no hat. Some are

simply stupid, others are bright, intelligent little fellows, who would

make good and useful men if they could have a chance.

The majority of these boys live at home, but many of them are wanderers

in the streets, selling papers at times, and begging at others. Some pay

their earnings, which rarely amount to more than thirty cents per day, to

their mothers--others spend them in tobacco, strong drink, and in

visiting the low-class theatres and concert halls.

Formerly, these little fellows suffered very much from exposure and

hunger. In the cold nights of winter, they slept on the stairways of the

newspaper offices, in old boxes or barrels, under door steps, and

sometimes sought a "warm bed" on the street gratings of the printing

offices, where the warm steam from the vaults below could pass over them.

The Bootblacks rank next to the newsboys. They are generally older;

being from ten to sixteen years of age. Some are both newsboys and

bootblacks, carrying on these pursuits at different hours of the day.

They provide themselves with the usual bootblack's "kit," of box and

brushes. They are sharp, quick-witted boys, with any number of bad

habits, and are always ready to fall into criminal practices when enticed

into them by older hands. Burglars make constant use of them to enter

dwellings and stores and open the doors from the inside. Sometimes these

little fellows undertake burglaries on their own account, but they are

generally caught by the police.

The bootblacks are said to form a regular confraternity, with fixed laws.

They are said to have a "captain," who is the chief of the order, and to

pay an initiation fee of from two dollars downwards. This money is said

to find its way to the pockets of the captain, whose duty it is to "punch

the head" of any member violating the rules of the society. The society

fixes the price of blacking a pair of boots or shoes at ten cents, and

severely punishes those who work for a less sum. They are at liberty,

however, to receive any sum that may be given them in excess of this

price. They surround their calling with a great deal of mystery, and

those who profess to be members of the society flatly refuse to

communicate anything concerning its place of meeting, or its

transactions.

A large part of the earnings of the bootblacks is spent for tobacco and

liquors. These children are regular patrons of the Bowery Theatre and

the low-class concert halls. Their course of life leads to miserable

results. Upon reaching the age of seventeen or eighteen the bootblack

generally abandons his calling, and as he is unfit for any other

employment by reason of his laziness and want of skill, be becomes a

loafer, a bummer, or a criminal.

For the purpose of helping these and other outcasts, the Children's Aid

Society was organized nineteen years ago. Since then it has labored

actively among them, and has saved many from their wretched lives, and

has enabled them to become respectable and useful members of society.

The Children's Aid Society extends its labors to every class of poor and

needy children that can be reached, but makes the street children the

especial objects of its care. It conducts five lodging houses, in which

shelter and food are furnished at nominal prices to boys and girls, and

carries on nineteen day and eleven evening Industrial Schools in various

parts of the city. The success of the society is greatly, if not

chiefly, due to the labors and management of Charles Loring Brace, its

secretary, who has been the good genius of the New York street children

for nearly twenty years.

The best known, and one of the most interesting establishments of the

Children's Aid Society, is the _Newsboys' Lodging House_, in Park Place,

near Broadway. It was organized in March, 1854, and, after many hard

struggles, has now reached a position of assured success. It is not a

charity in any sense that could offend the self-respect and independence

of its inmates. Indeed, it relies for its success mainly in cultivating

these qualities in them. It is in charge of Mr. Charles O'Connor, who is

assisted in its management by his wife. Its hospitality is not confined

to newsboys. Bootblacks, street venders, and juvenile vagrants of all

kinds are welcomed, and every effort is made to induce them to come

regularly that they may profit by the influences and instruction of the

house. Boys pay five cents for supper (and they get an excellent meal),

five cents for lodging, and five cents for breakfast. Those who are

found unable to pay are given shelter and food without charge, and if

they are willing to work for themselves are assisted in doing so.

The boys come in toward nightfall, in time for supper, which is served

between six and seven o'clock. Many, however, do not come until after

the theatres close. If they are strangers, their names and a description

of them are recorded in the register. "Boys have come in," says Mr.

Brace, "who did not know their own names. They are generally known to

one another by slang names, such as the following: 'Mickety,' 'Round

Hearts,' 'Horace Greeley,' 'Wandering Jew,' 'Fat Jack,' 'Pickle Nose,'

'Cranky Jim,' 'Dodge-me-John,' 'Tickle-me-foot,' 'Know-Nothing Mike,'

'O'Neill the Great,' 'Professor,' and innumerable others. They have also

a slang dialect."

Upon being registered, the boy deposits his cap, overcoat, if he has one,

comforter, boots, "kit," or other impedimenta, in a closet, of which

there are a number, for safe keeping. He passes then to the bath tub,

where he receives a good scrubbing. His hair is combed, and if he is in

need of clothing, he receives it from a stock of second hand garments

given by charitable individuals for the use of the society. Supper is

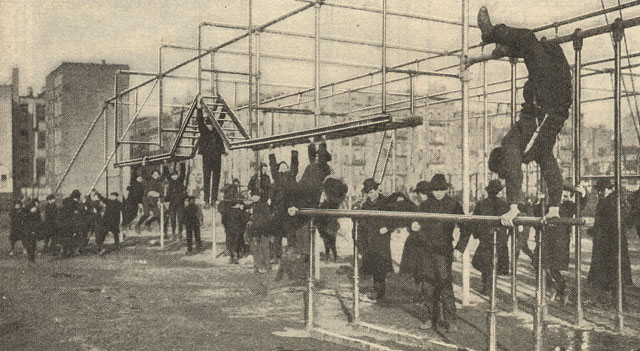

then served, after which the boys assemble in the class room, which is

also the chapel. Here they engage in study, or are entertained by

lectures or addresses from visitors. They also sing hymns and familiar

songs, and the sitting usually terminates about nine o'clock with the

recitation of the Lord's Prayer and the singing of the Doxology. After

this they may go to bed, or play dominoes for an hour or two longer, or

repair to the gymnasium.

On Sunday evening divine service is held in the chapel. Says Mr. Brace:

"There is something unspeakably solemn and affecting in the crowded and

attentive meetings of these boys, of a Sunday evening, and in the thought

that you speak for a few minutes on the high themes of eternity to a

young audience who to-morrow will be battling with misery, temptation,

and sin in every shape and form, and to whom your words may be the last

they ever hear of either friendly sympathy or warning."

"The effect on the boys," he adds, "of this constant, patient, religious

instruction, we know to have been most happy. Some have acknowledged it,

living, and have shown better lives. Others have spoken of it in the

hospitals and on their death-beds, or have written their gratitude from

the battle field."

The officers of the Lodging House use their influence to induce the boys,

who are the most notoriously improvident creatures in the city, to save

their earnings. They have met with considerable success. There is now a

Newsboys' Savings Bank, which began in this way: A former superintendent,

Mr. Tracy, caused a large table to be provided and placed in the Lodging

House. This table contained "a drawer divided into separate

compartments, each with a slit in the lid, into which the boys dropped

their pennies, each box being numbered and reserved for a depositor. The

drawer was carefully locked, and, after an experience of one or two

forays on it from petty thieves who crept in with the others, it was

fastened to the floor, and the under part lined with tin. The

Superintendent called the lads together, told them the object of the

Bank, which was to make them save their money, and put it to vote how

long it should be kept locked. They voted for two months, and thus, for

all this time, the depositors could not get at their savings. Some

repented, and wanted their money, but the rule was rigid. At the end of

the period, the Bank was opened in the presence of all the lodgers, with

much ceremony, and the separate deposits were made known, amid an immense

deal of 'chaffing' from one another. The depositors were amazed at the

amount of their savings; the increase seemed to awaken in them the

instinct of property, and they at once determined to deposit the amounts

in the city savings banks, or to buy clothes with them. Very little was

spent foolishly. This simple contrivance has done more to break up the

gambling and extravagant habits of the class than any other one

influence. The Superintendent now pays a large interest on deposits, and

the Trustees have offered prizes to the lads who save the most." The

deposits of the boys now foot up an aggregate of about $1800.

The boys are assisted to earn their own support. Says Mr. Brace, writing

in 1870:

"Through the liberality of one of our warmest friends, and generous

trustee, B. J. Howland, Esq., a fund, which we call the 'Howland Fund,'

was established. He contributed $10, to which other patrons added their

contributions subsequently. The object of this fund is to aid poor and

needy boys, and supply them with the means to start in business. We have

loaned from this fund during the year $155.66, on which the borrowers

have realized a profit of $381.42. It will be seen that they made a

profit of 246 per cent. We loan it in sums of 5 cents and upward; in

many cases it has been returned in a few hours. At the date of our last

report there was due and outstanding of this fund $11.05, of which $5 has

since been paid, leaving $6.05 unpaid."

The work of the Lodging House for seventeen years is thus summed up by

the same authority:

"The Lodging House has existed seventeen years. During that time we have

lodged 82,519 different boys, restored 6178 lost and missing boys to

their friends, provided 6008 with homes and employment, furnished 523,488

lodgings, and 373,366 meals. The expense of all this has been

$109,325.26, of which amount the boys have contributed $28,956.67,

leaving actual expenses over and above the receipts from the boys

$80,368.59, being about $1 to each boy."

The other institutions of the Children's Aid Society are conducted with

similar liberality and success. We have not the space to devote to them

here, and pass them by with regret.

It is not claimed that the Society has revolutionized the character of

the street children of New York. It will never do that. But it has

saved many of them from sin and vagrancy, and has put them in paths of

respectability and virtue. It has done a great work among them, and it

deserves to be encouraged by all. It is sadly in need of funds during

the present winter, and will at all times make the best use of moneys

contributed towards its support.

It employs an agent to conduct its children to homes in other parts of

the country, principally in the West, as soon as it is deemed expedient

to send them away from its institutions. It takes care that all so

placed in homes are also placed under proper Christian influences.