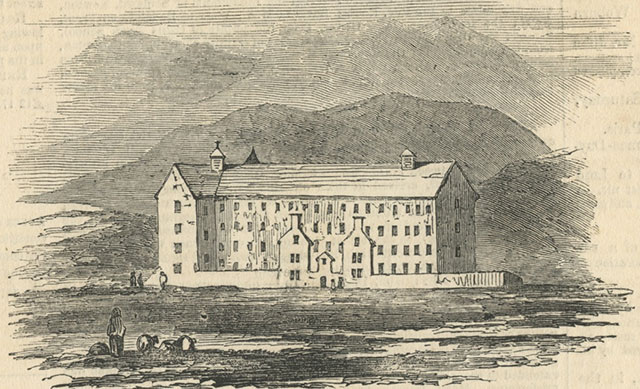

The Workhouse, Clifton

The Great Famine of 1845-1849 was not the first time that Ireland had seen famine.

There was famine in 1728-29 when the oat crop failed and the potatoes were not sufficient to make up the difference.

Another famine in 1740-41 was caused by a very cold winter when the potatoes froze in storage and the oat crop failed. About 10% of the population died.

Poor harvests also caused famine in 1817, 1822, 1836, 1837, 1841, and 1880-81.

A Brief Recap of The Great Famine of 1845-1849

1846300 people were evicted from the village of Ballinlass, Co. Galway, though none were in arrears of rent (13 March).

Three-quarters of the potato harvest was lost through blight (Summer/Fall).

The first deaths from starvation were reported.

1847

The Famine was at its height.

Typhus and other diseases spread throughout the country.

The potato harvest was blight-free but small. The corn harvest was good.

380 doctors were thought to have died in Ireland between the start of the famine and the end of 1847.

1848

1848 The potato crop was two-thirds the normal size. The Famine continued.

Cholera reappeared in November 1848 and continued into May 1849.

A Report to the House of Commons gave the following numbers for "Destitute Persons relieved out to the Workhouse for the Week ending July 29, 1848" - Total relieved out of workhouse:

Other Poor law divisions are listed. Totals were 19,564 cases with 51,546 persons

- Ballinrobe - cases 1,726 persons 5,118

- Partry - cases 1,104 persons 2,394

- Cong- cases 1,408 persons 4,516

- Hollymount - cases 1,641 persons 4,247

- Shrule - cases 1,454 persons 3,504

- Claremorris - cases 2,238 persons 6,768

1849

William Crolly, Catholic archbishop of Armagh, died of cholera at Drogheda (6 April).

Over a million people died during the famine, most from disease.

Over 90,000 evictions occurred during the famine.

Controversy in the Ballinrobe Workhouse in 1848

In 1848 Mr. William Murphy, the master of the Ballinrobe workhouse was accused of mismanagement and the murder of two of the workhouse inmates. Mr. R. Bourke's report to the Poor Law Commission stated that the majority of complaints had been concocted by the Rev. Mr.Peter Conway, curate of the Roman Catholic Church in Ballinrobe..

During Sunday mass on July 2 the Reverent Conway accused Mr. Murphy of misdeeds. The following Sunday at mass the Rev. John Morris, the parish priest, retracted the accusation made by Peter Conway.

Mr. William Murphy, a man Protestant man from Carlow, was arrested, imprisoned and accused of two murders

- The manslaughter of a girl named

Margaret (Peggy) Thornton age 11 daughter of Mary Thronton, Lough Mask, Kilmain. Mary

Thornton claimed that 2 or three weeks before Michaelmas (September 29) William Murphy kicked Peggy, gave her a "fist" and threw her to the ground.

He then ordered the girl taken to the hospital.

"The master then took hold of herself, shook and kicked her and locked her up in the black hole. Two hours later, he came with a woman and told her that her little girl wanted her. She then went to the hospital where she found her child dead. " (In Their Own Words: The Famine in North Connacht, 1845-1849)

- The death of a 7 (or 2 or 11) year old child named Patrick McGovern.

"Mary McGovern said she had been in Ballinrobe ... Three days before she left the workhouse, she saw William Murphy, master of the workhouse, beat with kicks on back the and on the head a boy of about 11 or or 12 years of age. He knocked him violently against a table in the hall." (In Their Own Words: The Famine in North Connacht, 1845-1849)

It was said that Patrick McGovern was taken ill with bronchitis on May 31. He was taken to the hospital where he died the same night. Murphy was accused of beating him and then burying the body.

A witness for Murphy was John Morris the R. C. Parish priest of Ballinrobe and the chaplain of the workhouse. Witness agains Murphy was the Rev. Peter Conway. It was stated that the jury was mixed Catholic and Protestant. Statements wer made that the Rev. Peter Conway was responsible for inciting the disturbances.

Murphy was acquitted.

An additional incident was a riot in the workhouse on July 13 when inmates of the workhouse tried to stop others let by the Reverent Conway from entering. The mob was attempting to break open the store rooms and distribute the meal and rations. Stones were flying in every direction. The military was called in - a large force of the 13th light dragoons and the 40th infantry responded immediately. Four or five inmates were accused of assault.

The excitement continued all the evening in the town, and we were under the necessity of having a police force left at the workhouse for the protection of the property, from the threats held out by the towns-people against the paupers in the house, and every one connected with the establishment. I think it would be a just punishment to stop out-door relief to the able-bodied of Ballinrobe electoral division, for a time at all events; and I have stopped the issued of bread to the school here, as the boys were amongst the most active in stone-throwing." Dr. Dempster to the Commissioners : - July 14, 1848. House of Commons Papers, Volume 54As a result of the riot the director of the Poor Law Commission called to stop rations for paupers receiving relief from the Union. Parties who joined in the riot were deemed Not "really destitute".

The major contemporary source for the happenings in Ballinrobe during the summer of 1848 are available from the Poor Law Union commission and so are kind of one sided. I found this report from the Ballina Herald of August 1946 commemoration what had happened 100 years before. Unfortunately I cannot seem to be able to pull up the actual paper and so have glued together bits and pieces of what was covered.

THE BALLINA HERALD. SATURDAY , AUGUST ---- WORKHOUSE MASTER CHARGED WITH MURDER (WRITTEN FOR THE "BALLINA HERALD" BY J. F. Q.) -----See Religion and Folklore in IrelandTHE BALLINROBE MURDERS

Murphy, the Master of Ballinrobe Workhouse, has been committed to the county jail on a warrant charging him with the murder of an inmate. We have definite information that the Carlow thug murdered and ---- two other inmates. The information has been laid before the proper quarter. Should he fortunately escape the penalty of the law for depriving human beings of their lives, he will derive benefit from his imprsonment , as he may learn from the example of the Governor, to display to those under his charge , patience, mildness and humanity.

--- WHAT HAPPENED? At Ballenrobe Petty Sessions before James Cuffa, Jeffrey Martin, Charles Arabin, R.M., John Finn, Francis Crea , Courtney Kenney, Esquire, and Capt. Fitzgerald Higgins

Michael Collins charged with riot in the workhouse, was discharged, the court stating that there was no evidence against him. Patk. McHugh charged Wm. Murphy, Master of the Workhouse, witn assault, and so was fined. £l and £1 costs, to be paid forthwith to the component.

Mr. Murphy was next charged at the suit of the ---- with tha murder of Patk. McGowan, a boy of 2 years of age, and a pauper in the workhouse. After hearing evidence, including that of the deceased's mother, a pauper, who was not permitted to ----- child dead or alive, the accused was committed for trial. Mr. George Acton appeared for him, Messrs. Myles Jordan, Ignatius Kelly and Patk. Glyn conducting the ----. Mr. Ignatius Keily informed the court that he was preparing informations in two other murder charges against Murphy.

PUBLIC INQUIRY DEMANDED At a public meeting in Ballinrobe, attended by Mr. Geoffrey Martin, Curraghmore, and other landlords, clergy, merchants and farmers , Mr. Michael Burke presiding, to protest against the tyrannical exercise of authority by the officials of the workhouse, a sworn inquiry was called for, and allegations of a most serious character, from murder to robbery and corrupt practices made. The only result was an influx of police, for which the ratepayers had to pay. The swearing of the Special Constables, and the appointment of more ----.

On Sunday a poor woman in Killawalla and her three children were found dead of hunger. The relieving officer did not visit them, the rate collector seized even the poor bed they had to lie on.

George Henry Moore, Esq., M.P., has been snatched back from the jaws of death. After his long and serious illness an improvement has set in.

BODIES EXHUMED At an adjourned sitting of Ballinrobe Magistrates a number of paupers from the workhouse were charged with riot and assault, and were returned in custody for trial at the Assizes. Then F. Crean, Eso., Coroner , appeared , and the Magistrates, Chief of Police, and a respectable jury proceeded to the workhouse burial ground, where they were led to believe lie the bodies of Patrick McGowan and Margaret Thornton, the paupers murdered by the Master, would be exhumed. There they remained in the rain at least two hours, in the hope that officials would point out the graves, but to their great astonishment they could get no information as to where they were buried. At length the Clerk came forward, and said he would not allow the paupers exhume the remains, and that he was desired by the Vice Guardians not to give any information. The Magistrates, Coronor and ratepayers went off disgusted. In the apparent disregard for authority exercised by the officials. Subsequently there was an exhumation order, and after two doctors had examined the bodies a number of witnesses were heard, after which the jury found they believed death was caused bv violence. The Coroner then issued two further warrants for murder against Murphy. At ths Assizes (for which there were 17 murder cases) three bills for murder were sent up against Murphy, but the Grand Jury ignored two of them, and found one for manslaughter, in the case of Peggy Thornton, and a grand jury of landlords and other enemies of the people was packed for him, viz.: Wm. Kearney, Ballinvilla (foreman) , James Knox Gore, Ormsby Elwood, Edwd. Daane, J. F. Burke, Wm. Ruttledge, Christopher Acton, Matthew Gibbons, J Cannon, Wm. Jonas, Jas. O'Don----, and Wm. Bola.

Then, light of me Irish Parliamentary ---- and darling of me Catholic Clergy ---- SJ , the notorious Judge Keog , who ---- his way to the bench and became a second judge ---- as a hanging judge, and a ----- Catholics and their clergy, though he was a Catholic, ------- and submitted the priests called to as blackguardly an examination as could be imagined, and was complimented by tha Judge for the ----- of it. He was assisted by George O'Malley, Q.C., Hawthorn Lodge, and though the evidence was conclusive, the jurv , telling the Judge that there was no necessity to charge him, acquitted without leaving ---- box.

FREEDOM FOR MURDERERS To the exclusion of our regular features, We devote most of our space today to the Ballinrobe manslaughter charge, feeling that the vast importance of the trial, not only for the due administration of the law, but for the future protection of the destitute poor. I ------ to go into the care of tyrant; , will have a good effect. The guilt of the prisoner was established to the hilt, and no doubt ------ precipitated verdict was the outcome of the forensic eloquence of Mr. Keogh. We are pretty convinced, and so are the public, that Peggy Thornton's death was hastened by the intemperate conduct of Murphy, and that he is also responsible for the deaths of the ether two boys who sleep in pauper graves at Ballinrobe workhouse. The trial is now over. It will do a great deal of good. The result will not be lost on the public at large, or those charged with the government of the country, and let us hope that never again will we hear of officials savaging paupers and burying them immediately. An all-seeing God! Look down on Your poor. ("Connaught. Ranear ").

A NOVEL DEPARTURE Subsequently the Mayo news- papers publishad a petition that Wm. Murphy, master of Ballinroba workhouse, had sent to the Lord Lieutenant requesting him to have criminal proceedings taken against a number of magistrates, priests and newspaper men who, he said , were instrumental in having him wrongfully indicted for the murder of paupers in the workhouss. His Excellency acknowledged its receipt. Subsequently Sir Robert Blosse, Baila , in a letter to the "Ranger " said that as foreman of the Grand Jury at the Assizes he felt called upon to resent the reflections on that body contains in the memorial of Murphy. He resented the allegation that a true bill was wrongly found against him , and went on to refer to the facts of a case that was outstanding the bills for murder against an official puicl [?] by the ratepayers.

At Mayo Summer Assizes. 1848 . Baron Lefroy heard an issue transmitted from the Queen's Bench about Lord Lucan's rates. For the defence it was pleaded that as "immediate lessor " " he was not responsible for rates on holdings valued £4 and that as he was not the rated person he was not liable. Under the law as it then stood the landlord was liable for holdings valued under £4, and these rates he paid, and his Counsel ---- on the quibble that he was not liable for the evicted lands when the tenants' names were in the rate books. He had a sympathetic court, and under a compromise there was iudgment for £508.

Ballinrobe. Swin---- and Westport Guardans had similar cases and fared likewise. The very efficient Clerk of Castlebar Union, Penrose, the Quaker from Carlow, had no entry at all in the books against Lucan, except "immediate lessor" though he was well aware that he had evicted the tenants and was cultivating their lands, added the report. The Grand Jury decided to send addresses to both Houses of Parliament complaining that the Poor laws were oppressive, that the Dublin authority acted in a high-handed manner in displacing the elected Guardian; and substituting; paid ones who showed no regard for the interests of the ratepayers and the poor; that their regime had already created a scandal that should be the ones removed.

POTATO CROP IN RUINS Mr. John Denis Browne, Mount Browne, wrote to the newspapers in August. 1848, that the most sanguine could no longar entertain a doubt as to the potato crop in Mayo going already in ruins, and that consequently a new series of miseries, perhaps tenfold greater than in the past years, was assuredly in store during the coming winter and spring. He urged that immediate steps be taken. Parliament being then sitting, to area measures calculated to give employment, and for carrying out an extra ---- system of emigration . "The formation of railroads throughout Ireland, together with an extensive system of emigration, appear to be the only means now lait[?] for affecting an important mitigation of our calamities. The former would izni[/] towards the immediate development of the wonderful resource or our land while the lane [?] would turn to some useful account those numerous, expensive and useless colonies which are ------ the strength ----- the British Empire. " The ---- a hundred labourers improved a new Canal from Louuh Co. . to Loush Mask. "

Mayo 100 years ago. August 3, 1946 Ballina Herald from Ballina, Page 3

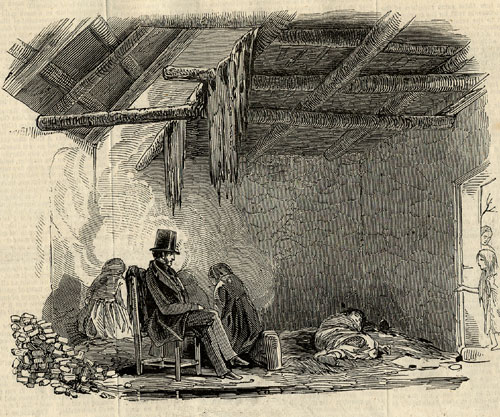

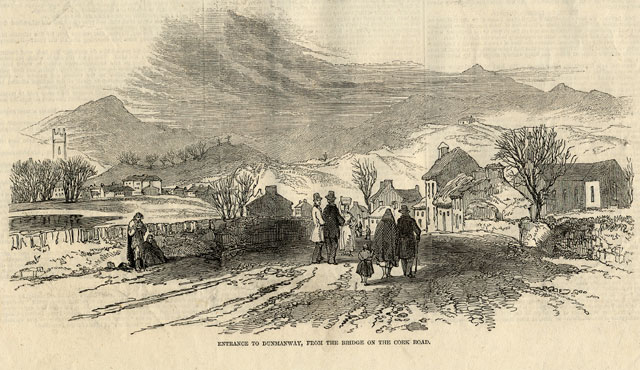

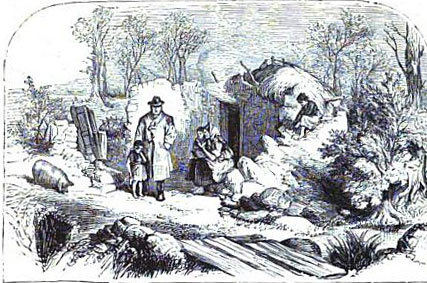

The Ballinrobe workhouse was built in 1840-42 to house 800 inmates.

The Great Famine

The famine affected all of Ireland. However, some areas suffered more than others. Rural areas suffered more than the towns and cities.

There was a big surge in the population of Ireland in the early part of the nineteenth century. In fact, the population nearly doubled between 1820 and 1841. This huge increase put tremendous pressure on the subsistence economy of the times as land was divided into smaller and smaller plots. By the 1840's the average density on cultivated land in Ireland was about 700 people per square mile, among the highest in Europe.

The major portion of the agricultural population on the land were "cottiers"; farmers who rented small plots of land. The major portion of the cottiers were Catholic who rented from Anglo Irish landlords. Cottiers rented an average of five acres of land and were often forced to seek other employment to supplement their income.

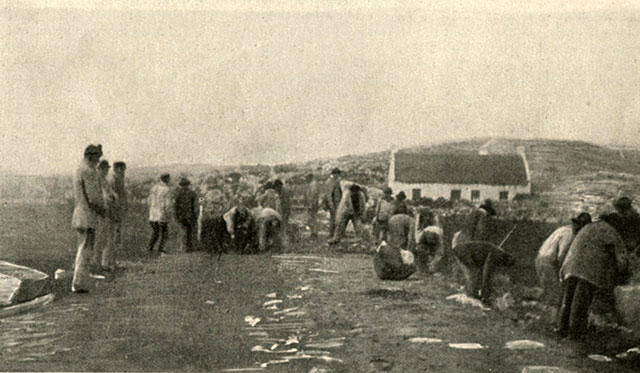

The cottier's cottages were built with local stone or turf and thatched with rush or straw. Many cottages did not have windows and chimneys. Windows, when they existed, were often too small for a man to put his head though. There was often, but not always, a hole in the roof to let out smoke. Ventilation was always bad. Pigs, poultry and other animals lived with the family, often sleeping in the same room. Due to landlord oppression Catholics were reluctant to beautify or improve their houses. The houses could not be over a certain height or the rent was raised. Since the door could not be more than five foot eight inches high, there was a step down into the kitchen to allow for extra space. See Photos of the Old Village of Mochara which contains photos of the ruins of the cottier's cottages in Mochara.

In the cold and damp environment the only form of heat for cooking and warmth was a peat or "turf" fire.

The potato was the major food crop of the impoverished Irish because it was economic, easy to plant, and grew well in the rocky soil. Any wheat, barley, and/or oats that the cottiers grew or pigs that they raised were sold to pay the rent. Everything was used, potato shins and surplus potatoes were fed to the pigs, and pig manure was used to fertilize the potato fields.

By 1820 the potato was the staple the cottiers diet in Mayo. The potatoes was seasoned with salt and eaten three times a day. According to several published reports, adult males ate up to fourteen pounds of potatoes a day. Women and older children ate about eleven pounds. The only other food was cabbage, fish, an occasional fowl, eggs and some dairy products. It is estimated that seven million tons of potatoes a year were required to feed the population of Ireland in the 1840's. As awful as this diet sounds, the potato eating Irish were better nourished and healthier, than other populations in the rest of Europe at the time.

The Irish dependence on the potato as their major food crop was the main reason for the devastation that occurred when the potato crop failed.

There had been localized and minor failures of the potato crops before 1845. However, until 1845 the potato had been more reliable than grain.

The potato blight was a disease that first appeared on the east coast of the United States in 1843. By 1845 it had spread to the mid-west in the United States. The blight was a fungal infection, which thrived in mild and damp climates. The spores were carried by the wind. Guano, imported as fertilized from Peru to the United States was probably the source of the fungus. Infected potato seeds were exported from the United States to Europe. The blight effected potato crops in most of Europe, but was particularly bad in the Low Countries, Germany and Ireland.

In 1845, Ireland lost about a third of its main crop which was usually harvested from October to November. Very few people in Ireland actually died from starvation in the winter of 1845-46. Continental Europe was in a much worse state that winter. No one really knew that first year what had caused the crop to fail. Most botanists thought it was a wet rot brought on by a particularly damp summer. No one really thought there would be a problem with the next year's crop.

The blight reappeared on the west coast of Ireland in the summer of 1846. Propelled by the prevailing winds, it spread at a rate of about fifty miles per week. By August it had devastated about three-quarters of the potato chop. Food prices soared beyond the reach of the poor. Grain, that could have fed the population of Ireland itself, was exported from Ireland to England to pay rents to the landlords.

The first deaths in Ireland were reported in October of 1846. There was no national system for relief. Local systems failed to function adequately. By December people started dying by the thousands. The Irish who had immigrated to America before this period sent hundreds of thousands of dollars to help the famine relief. The Quakers established relief committees in November of 1846. It was not enough.

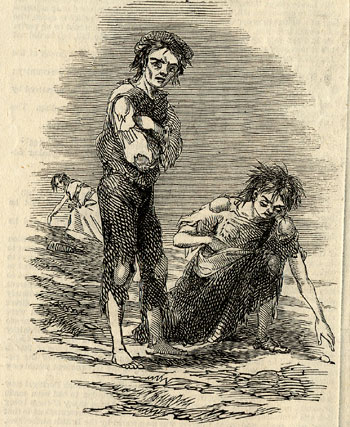

Very few people actually died of starvation, but they became so undernourished that they fell prey to all types of diseases, especially "Famine fever". Dysentery, diarrhea, measles, and tuberculosis were epidemic as the population became more and more malnourished. It got worse as the sick and starving crowded into towns seeking relief from the workhouses. According to the Reverent Phew:

"About three or four hundred of the most destitute have crawled into Ballinrobe every Friday for the last month, seeking admission to the workhouse or outdoor relief and though they remained each day until night, standing in wet and cold at the workhouse door, craving for admission, they have got no relief."In June 1847 fever and dysentary raged in Ballinrobe and many of the other towns in the area. Remedies for fever and dysentery were unknown and quarantine was impossible.

The dead were often buried where they lay on the side of the road. Workhouse dead were buried in mass graves.

Soup kitchens were instituted in July 1847. Mortality fell.

The summer crop of 1847 did not fail. However, it was meager because there was very little seed available for planting. Many declared the famine over. There was, in fact, no real recovery. Most of Ireland continued to suffer from disease and starvation.

The potato blight returned in July of 1848. The west of Ireland had a repeat of the disaster of 1846. In November 1848 cholera broke out. By the time the epidemic was spent in 1849, thousand more had perished.

In addition to the lack of food, in 1847 absentee landlords began evicting tenants who were unable to pay their rents. Mass evictions occurred, especially in County Mayo and County Clare. By 1848 Lord Lucan was inforcing wholesale evictions from his estates near Castlebar and Ballinrobe. Between 1849 and 1854 nearly 50,000 families were evicted from there homes.

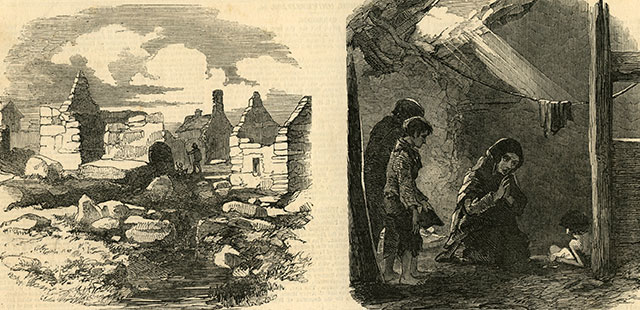

Cottages were "tumbled" that is, pulled apart by the landlord's gangs. Roofs were removed and houses leveled. In the Union of Kilrush in County Clare 2,891 houses were leveled in 1848-49. The inhabitants were turned out to fend as best they could.

The absentee landlords looked upon the famine and the cottiers inability to pay the rents as an opportunity to clear the land for more profitable enterprises, like pasture.

In Ballinrobe Parish alone 2000 people were removed from their homes and the cleared land was turned into pasture.

All over Ireland, those who were evicted did not want to enter the disease-ridden workhouses. They turned instead to temporary shelters, begged in the cities or emigrated to England, America or Australia if they could afford it. Many of those evicted in County Mayo died by the roadside.

In Lights and Shades of Ireland, written in 1850, Asenath Nicholson says,

"Perhaps in no instance does the oppression of the poor....come before the mind so vividly, as when going over the places made desolate by the famine, to see the tumbled cabins, with the poor, hapless inmates, who had for years sat around their turf fire, and ate their potato together, now lingering and ofttimes wailing in despair, their ragged barefoot little ones clinging about them, one on the back of the weeping mother, and the father looking in silent despair, while a part of them are scraping among the rubbish to gather some little relic of mutual attachment....then, in a flock, take their solitary, pathless way to seek some rock or ditch, to encamp supperless for the night."

Brian Smith in Tracing Your Mayo Ancestors says,

" The country was significantly affected by the Great Famine of 1845-1847, which resulted in the death or emigration of 30% of the population by 1851."

It is not known for certain how many died and how many emigrated, but the population of Ireland is estimated to have fallen by 2,400,000, more than 25% of the pre-famine population. Deaths were most common among the very old and the very young (children under five). Emigration from Ireland to Great Britain, Australia and the United States had started long before the famine, but by the end of 1846 the numbers greatly increased. Between 1846 and 1856 about 1,800,000 emigrated from Ireland. Most cottiers had never traveled more than 20 miles from their home, so the trip across the ocean must have been extremely traumatic.

The 1852 potato crop was healthy, although the yield was not as high as the pre-famine crops.

American corn meal became a common food staple. While some things, such as diet improved in western Ireland after the famine, there were still reoccurring episodes of potato blight. The blight reappeared in 1860-2, 1879, 1890, 1894 and 1897. These later blights did not cause as much devastation because of the availability of alternative food sources. Wet years caused a scarcity of dry turf for fires and produced outbreaks of typhus, pellagra (a desease causing skin irritations, diarrhea and nervous disorder), famine fever, and other diseases. The workhouses were full and western Ireland remained very poor.

Penelope Byrne Langan, the mother of Maggie Langan, was baptised in 1836 in Shrule parish ten years before the famine started. Penelope's parents, Michael Bryne and Penelope Naughton, lived in the hamlet of Mochara where Penelope (Nappy) Naughton Byrne was listed as the holder of a ¹ share of 64 acres of land and a house in Mocorha in 1856. The people living in Mochara in 1856 fit the discription of "cottiers". Michael Byrne and Penelope Naughton Byrne had at least four children, Penelope, Winifred, Peter and Thomas who lived to be adults.

I don't know where Mathias Langan and his family lived before he moved to the town of Ballinrobe. However, they were most likely originally from somewhere south of the town of Ballinrobe near Shrule or Cong. The Langans were also most likely cottiers before they moved to Ballinrobe.

While the population in the west of Ireland suffered more than other parts of the country, people in towns generally suffered less than those living off the land.

Clearly the town of Ballinrobe grew between the time of the Tithe Applotment in 1827 and the Griffith in 1855. A brief look at any part of the town shows many more dwellings in 1855 than 1827. This was probably a reflection of people moving to town from the countryside during the famine. There were many new names in the town between the Tithe and the Griffith. See Griffith Valuation.

The Walshes most likely lived in or near the town of Ballinrobe at or before the time of the famine.

John Walsh, the father of Joseph Walsh, had a strong association with people in the town of Ballinrobe who were craftspeople or who ran small bussinesses.

Post Famine Emigration

The great reduction in the population during the famine ironically benefited the survivors, enabling them to greatly improve their standard of living.

Bad harvests returned in 1877, 1878 and 1879. For whatever reasons, between 1881 and 1890 about 400,000 emigrants left the west of Ireland. The great majority of emigrants consisted of noninheriting offspring, single men and women in their teens and twenties.

These emigrants included Michael, Mary, James and Thomas Walsh (the sons of John and Fanny Walsh), and Martin, Pat and Maggie Langan.

Mathias Langan, his wife and two youngest children did not emigrate until 1892. Joseph Walsh and his sister, Fanny did not emigrate until 1894.

Although there are no actual records for the rate of emigration from Ballinrobe in the latter part of the century, there are indications that it was high. The later Griffiths in Ballinrobe show that there were a significant number of vacancies listed in all parts of town. Since the birth rate seems relatively high, I can only assume that these vacancies were a reflection of emigration.

The 1901 census indicates an even larger decrease in the town's population.