| Irish Peasants 1897 | |||

| HOME PAGE - Walsh/Langan Introduction | |||

|

The Peasants' Ireland,

By Clifton Johnson,

Outlook 1897

The following photographs and text are from an article about peasant life in the village of Lisonter, Connemara, County Galway, Ireland in 1897. Lisonter is near the town of Recess (which is referred to by the author). Recess is about 20 miles from Mochara in County Mayo. Although Connemara was held as an example of the worst of the poverty in the West of Ireland peasant life in Lisonter and Mochara must have been much the same in 1897. Life in the town of Ballinrobe may have been somewhat better. However, life in most of the small villages surrounding Ballinrobe would have been pretty much the same as that described in the village of Lisonter. One difference is that the area around Mochara and Ballinrobe is less hilly than around Lisonter. Maggie Langan Walsh left Ireland circa 1890. Joseph Walsh left Ireland in 1894. However, things had probably not changed much between the time they left and 1897. The writer shows some anti-Irish prejudice. However, ultimately I fell he is more sympathetic than many other English writers.

|

|

|

|

"A Cottage Interior" |

|

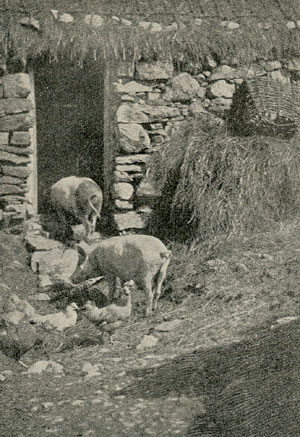

"Members of the family" |

|

"A Load Of Peat on the Way to Town" |

|

"A Peasant Home" |

|

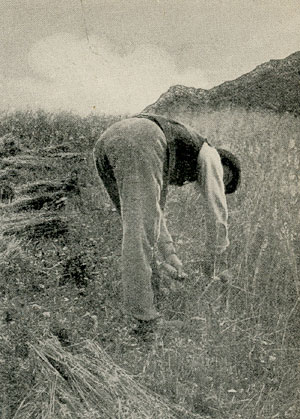

"Harvesting Oats" |

|

"On the Bogland at the Close of a Day of Wind and Storm" |

|

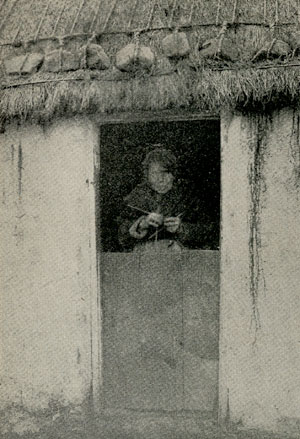

"A Knitter in Her Home Doorway" Notice the rocks holding the thatch. |

|

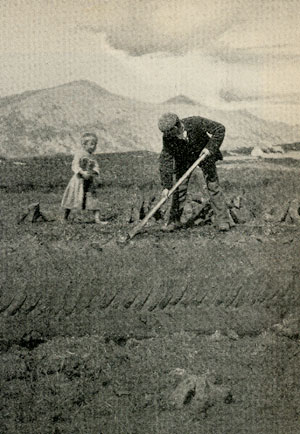

"Cutting Turf in the Bog" |

|

The Peasants' Ireland

By Clifton Johnson Outlook 1897 As compared with the other divisions of Britain, Ireland had a rundown, out-at-the-heels look that is depressing. Both the country districts and the towns show marked signs of dilapidation, decay, and even thriftlessness. There are broken walls and litter in the neighborhoods of all the villages and cities, and the land looks as if tillage was neither energetic nor careful. I made the trip across the island form Dublin to Galway in a recent August. The country as seen from the car window was uniformly flat, and much of it was bogland- wide, brown, unfenced grazing wastes with black stacks of peat scattered over them and dark pools gleaming in the cuttings. Now and then there were places in the bogs where the heather lay in great masses of pink blooms, but it was only in patches, and never covered acres and miles as in the Highland moors of Scotland. We passed many little gray stone towns and many ruined towers and castles. The cottages along the way were small, with whitewashed walls, thatched roofs, and a good deal of filth and rubbish about the yards. In the fields were numerous cattle feeding, and donkeys, goats, and geese were common. These fields were pleasantly green, and looked fairly fertile. The old hedgerows that bounded them were at this season full of fruit- little hawthorn apples with so strong a reddish tinge as to give the bushes the appearance of being of bright blossoms. From Galway I went northward into a more rugged region, where the bogs bordered desolate lakes and the stony Connemara mountains rose in ragged outlines. This railroad on the west coast had been built only a year, and it gave easy access to a district where the Irish peasant could be seen unaffected by the march of modern improvement. Not that life there is exceptional; for what is true of Connemara is just as trued of many other parts of Ireland, and even in the sections most favored the peasant life is exceedingly primitive and the home surroundings very poverty-stricken and dubious. At a place called Recess I left the train, and found myself on the platform of a lonely little station in the midst of bog. No houses were in sight, but a man with a jaunting-car took me aboard and raced his horse for a hotel a mile away as if he was going to a fire. I hung on for dear life; for a jaunting-car seems built to throw its passengers off every time it rounds a curve. It is a shaky two-wheeled vehicle, very lightly built, with a seat on either side facing outward. You sit directly over the wheel, and you feet rest on a swaying step that hangs down nearly to the hub. It is the national vehicle in Ireland, and you see these spidery cars everywhere, both in town and country, and their drivers seeded always to have a mania for going about with a breakneck impetuosity quite alarming to a stranger. At the hotel- a whitewashed stone building in a little wood on the edge of a lough- I was met at the door by a slick waiter with and expansive shirt-bosom and a posy in his buttonhole. He gave one the impression that this was a very "tony" establishment; but the interior was rather forlorn, nevertheless, and had an ill-kempt look, with its stained wall-paper, decrepit furniture, and an odor that suggested a need fro scrubbing and renovation. That same evening I walked across the bogs up a hillside. The earth was spongy and yielding, a mass of moss with thin growths of grasses, clumps of heather, and a scattering of reeds. Here and there it was brightened with touches of delicate yellow-green, but the general tone was brownish and somber. Frequent gray boulders thrust up into view. These became more numerous as the land rose higher, till I went over a ridge where the soil was thin and strewn everywhere with shattered rock. Beyond this ridge was a little huddle of houses with the accompaniment of tiny stone-walled fields running down into a green valley. The houses were low, and their walls and thatched roofs were dark-colored and so like the surrounding bog that they seemed not the work of human beings, but some huge mushrooms growths of nature. Not a tree was in sight, nor anything related to a tree, save a few little osier beds in the garden patches that were cut off each season and woven into creels. As soon as I began to descend the ridge, a barefoot woman with a shawl over her head and a big baby in her arms came hurrying to me from on outlaying cabin of the village. She arrived breathless and thrust a bit of green marble into my hand, and called down blessings on my head in her fervent jargon. All this was intended to soften my heart and coax forth a tip. She told with pride how fond the little "Pat" in her arms was of money- how, if he saw strangers coming he would run to her and say, "Gentlemens! Gentlemens! Come and get money". When any one gave him a bit, he would say "Thank God, I've got my money." He was two years old, but she said he made her carry him everywhere she went. Even if she had a big sack of peat on her back she must take him along under one arm. Once, she said she gave him a little flat stone and tied it in the corner of her handkerchief, and he carried it about in his bosom all day and called it his money. Rough, narrow, stone-walled lanes crooked and rocky, connected the cottages. Blackberry-bushes, thickly dotted with ripe fruit, straggled over the walls. I thought it a wonder, in such a starved-looking community where there were plenty of children, that the berries were left to ripen. All through that region blackberries were plenty and delicious, but I was told that few were ever picked. While I was eating berries in a village lane, a young man approached me, said, Good-morning to your honor," and jumped over a wall and snapped off some more clusters for me. After that he walked about in my company, a self-constituted guide. But he was a quick, intelligent fellow, and I did not object. His name was Michael. Just above the village was a quarry, and many great blocks of stone, curiously grained and colored, were lying round about. This quarry had been a short-lived experiment, and was not worked now. Michael said it had given employment to a number of the village men, and there were paid half a crown a day, while some men were brought form away "earned as much as five shilling, sir-they did, sir!" Now there was no employment to be had in the neighborhood. The villagers could only work their little farms or leave. About all the young men and young women went away to the towns or to America. Michael had two brothers in Boston. They did not write what they were doing, but every year they sent home some money to "the old man", his father. The rents of these little farms were form two to six pounds. Each cottager grew a little field of oats, another of potatoes, another of grass, and some raised patches of cabbages or turnips. These crops were grown mostly on the thin-soiled, stony hillsides. If a man took a field in the meadow below, his neighbors thought he was too well off, and accused him of an inclination to put on airs and ape the aristocracy. Besides all this, it added an extra pound to the rent. Most of the people kept two or three cows, several sheep, and a few hens. In some cases they owned a pony or a goat or a flock of geese. There were also two half-grown pigs that frequented the village lanes. They were sharp-nosed, long legged creatures, nimble of foot, and apparently capable, in their wanderings, of picking up their own living. When at home they lived in their master's house. This house had but a single room, and the pig-pen was in one corner. Aside from the pigs, the family was composed of a man and wife and three or four children. Their abode was windowless, and light came in only through the two doors and possible chinks in the walls. Michael said that in old times they used to keep pigs under the bed, but they did not do so in this village of Lisonter nowadays. The people sold their poultry at the hotel, and other produce they took to market. At Christmas a goose was at times killed for the family table, and some occasionally indulged in mutton. Now and then they bought fish, and bacon was more or less familiar, but many of them never knew the taste of beef. Most families have oatmeal frequently, and all of them eat potatoes. Indeed, potatoes stand chief on the Irish peasant's bill of fare. The oats raised are fed out to the stock, and the oatmeal for house use is bought, a bagful at a time. Flour is purchased in the same way, and bread is baked in a flat kettle on the hearth. They do not make butter or cheese, for the cows do not get enough feed to make it worth while. The milk is drank with the potatoes and oatmeal. Since the railroad came, tea has become a family necessity, and all the eggs the hens lay in exchange for it. About the only farm tools to be found in Lisonter are spades- primitive, narrow-bladed, and one-sided, but apparently effective. No such contrivance as a plow has ever been seen in the village. They dig their fields over by hand. Potatoes are planted in rows that are nearly three feet wide, known as "drills". The space between each drill and the one next it is dug out like a ditch, and serves for drainage. The potato tops grow in a spindling jungle on the drills, much too close together to do well. Crops are not rotated, but are grown over and over on the same ground, and are never what they might be. Often the potatoes fail to grow except scatteringly, in which case cabbage-plants are set to fill out the blanks. This year had been too wet, and the "blight had come too early." Michael and I climbed far up a crag at the back of the hamlet to get a view. Several of the village children tagged after all the way, taking turns at begging. "Please give me a copper, sir- only one, sir", they said, and refusals had no effect whatever on them. One boy of eight, still in skirts, had a baby on his back- a solemn, watchful baby that let out never a sound. The boy did not seem to mind his burden, but climbed about everywhere with the rest. These shoeless children were sure-footed and nimble as goats, and skipped about the rocky hillside just like some wild creatures of the bog. I went high up where I could look over long stretches of the dreary marshlands that are omnipresent in that region, spotted and linked all over by the loughs, large and small. Far away in the west one could catch a gleam of the sea, while in the near landscape, all about, the mountain crags were darkling, and in the hollow close below were the hovels of Lisonter and their little patchwork of varied colored fields. On the way back through the village a stout, fairly well dressed young man got off the wall where he had been loafing, and came hulking after me. "Please, sir, give me the price of an once of tobacco," he said. The children beggars followed me far down the hill. Begging seemed to be constitutional with the Connemara peasantry, and I always had a persistent group in my wake every time I visited Lisonter. When I approached the village a day or two afterwards, a woman came hurrying across two or three fields with a bundle of cloth on her arm, and greeted me with, "Good-marnin', sir, an' sure it's a fine marnin', sir." Then she spread out the cloth along with a few coarse socks and begged me to buy. "Plaze, sir," she said, "buy the friz, for the love o' God and a poor woman who's lost her b'y an' pit him in the grave only five weeks past." She went on to tell me that she had borrowed the money for the boy's burial from a poor neighbor woman who must be paid now, and she with nothing to pay. Her husband had gone far away to get work, "but he soon come back, for there were a big weight on his heart and he could eat nothing at all, at all." She spoke of her eight children- "Four of 'em I've given to God, and four of 'em's alive- God bless 'em." I went across the fields to her cottage squatted among the stony patches of oats and potatoes. Like the rest of Lisonter cabins, its stone walls were loosely chinked with peat, though once in a while a house showed traces of whitewash. Roofs were of sedge tied on with straw ropes thickly drawn over and fastened to pegs under the eaves or to stones hung along the edges. The thatch was renewed every year. It would last two if new ropes were put on each time, but few would do that. The chimneys were insignificant and hardly showed above the roofs. Peat was the only fuel burned. It was all brought from the bog, a sack at a time on the women's backs. The Lisonter folk never saw coal till some was brought for use in an engine at the quarry. Then they thought it was rock, and it was a great wonder to them that the stuff burned. Most never saw a railroad till the local one was put through, the year before. As soon as it was finished they all must ride; but when it came to getting aboard, they felt they were taking ttheir lives in their hands, and at the start the old women were all jumping up and screaming they would be murdered and their fiends would never see them anymore. The woman with the cloth to sell showed me into her cottage. The door was low, and I had to stoop to enter. She hunted up a level place on the dirt floor and set out a chair for me. A dim fire burned among the rough stones of the fireplace, and sent a little smoke up the chimney and a great deal of smoke into the room. The kitchen was full of flies, and it had the odor of a stable. The floor was much littered with heather and rushes that had been brought in to bed the cow and calf that had a home in one end of the kitchen. On some tattered blankets thrown over a heap of sedge near the fireplace, two of the children slept. The rest of the family had a bedroom beyond a thin partition. My hostess, in the midst of her talk with me, pulled a short pipe from her pocket and made much mourn that she had no tobacco to fill it. She said it was very comforting. "It's loike medicine to me." My former guide, Michael, had come up to the cottage and was talking outside with some of the beggar children. The woman saw him and sent out her ragged little girl, Bridget, to "borrow the loan of a pipe" he was smoking. Michael lent the pipe readily, and as the woman whiffed she blessed him again and again. When I left, she blessed me likewise, saying, "Long life to ye! An' may your journey home be better than the one over. God bless ye, an' give ye a safe crossin'!" In a cabin a little further up the hill lived a woman all alone. She was still young and not unattractive. Her husband had gone to America, and he would have taken her with him, but she would not leave. A letter had come from him only the week before in which he sent L3, and the villagers thought that was doing pretty well. Her cottage was hedged in by great growths of nettles that flourished all about. The roof leaked and the cabin had but one room, which the woman shared with two cows. I looked in, but did not care to enter, It was more like a floorless stable, that had not been cleaned for a week, than a human habitation. The house at some time had had a single window, but this was now loosely closed with stones. Most of the Lisonter houses, however had at least one window, and several of them had two, though occasionally these lacked glass. All were small, varying in number of panes from one to four. Mud and refuse was almost universal about the doorways and a "midden" (manure-heap) was always handy neat the house front. A skeleton horse was feeding in a waste near the quarry; some old men, working days past, were sunning themselves on the rocks; one or two old women were sitting or leaning on the walls near their cabin doors, some in idleness, some knitting. In the oat-fields the men were reaping laboriously handful by handful with their sickles, and the barefoot women followed behind to bind the sheaves. The women gleaned over the ground as they worked, and picked up every straw. I spoke with one man, and he said he had two or three acres in his farm, but it was very poor land, and in a wet year his crops were well-nigh failures. Still he considered himself better off than most of his neighbors. Nearly every day I saw the children going to school in the morning, and met them returning in the evening. Their aspect had the same untamed wildness then that it had as I saw them running about the bogs and crags that surrounded the home village. The school-house was four miles distant along a desolate road winding through the dun marches. The children went barefoot and bareheaded, except for a few of the older boys, who wore caps. They each carried a piece of dry bread for their noon lunch, and that was all the food they had till they returned home late in the afternoon. But, with all their hardships, they looked sturdy and healthy. Probably weaklings do not survive long. Once I noticed that a boy in a group of children returning from school carried a book, and I asked to see it. It was a most forlorn little third reader- a wreck of a book- covers broken, marked and greasy within, and many pages gone or torn. The school-house was a bare modern building with gray plaster walls. It stood in the center of a rough, rocky yard, that was surrounded by a high stone wall. Outside the inclosure all was bog, save for three or four houses with their little fields straggling along the road not far away. One of the things I looked specially for in Ireland was the shamrock. I had no clear idea of what it was like except that it was green and triple-leaved, and I supposed it was a native of the bogs. Often in my Bogland wanderings I saw a coarse, fleshy plant that grew in thin clumps where the water gathered in pools. The leaves were three-parted, but larger that the largest clover. Still, I thought it must be a shamrock, and picked some of it and showed it to a native. The native did not even know the name of my Bogland weed, but he stooped down and showed me some of the true shamrock growing by the roadside. It is an insignificant yet delicate little plant that loves to grow on stone walls and along roadways where the soil is poor and often scraped away. It was more like the downtrodden white clover that one finds growing in hard paths than anything else. The peasantry feel a real affection for the shamrock, and it is beautiful in their eyes. Like themselves, it lives amid hard conditions, and it seems pathetically appropriate that it should be the Irish national flower.

| |

| If you have any suggestions, corrections, information, copies of documents, or photos that you would like to share with this web site, please contact me at maggie@maggieblanck.com | |

| If you wish to use any of the images or information on this page please feel free to do so provided that you give proper acknowledgement to this web site and include the same acknowledgments that I have made to the provenience of the image or information. Thanks, Maggie | |

| © Maggie Land Blanck - Page created 2004 - Latest update, April 2011 | |