|

|

HOME -

Goehle Introduction -

Blanck Introduction -

Erxmeyer -

Petermann Introduction -

Immigration

German Immigration to the United States In the United States today there are more descendents of German immigrants than any other European ethnic group. From colonial times until the First World War the was a constant stream of immigrants from Germany to the United States.

Germany Prior to 1871 Prior to 1871 Germany was not a nation, but a series of independent German states. Consequently most Germans tended to identify themselves as being from Bavaria, Brunswick, Freisland, Hessen Darmstat, Oldenburg, etc.

Emigration Germans had been arriving on America's shores as early as the Jamestown settlement in 1607. Germans founded Germantown, Pennsylvania in 1683. In general, Germans emigrated to find adventure and greater prosperity. However, Germany, particularly, Bavaria, was hit by the potato famine in the mid 1800s. Some German immigrants sought political and religious freedom. In 1848 there were Germans fleeing political problems in Germany. Although the Potato Famine in Ireland is much better know in America there was a similar problem in the Lowland countries and in Germany. In the mid 1840's a great parallel stream of immigrants from Ireland and Germany arrived on America's shores. Bavaria which had become very dependent on the potato was at particularly hard hit with the failure of the potato crop. Whole village from Bavaria, most of them traveled by carts to La Havre, Amsterdam, Hamburg, or Bremen set sail for America. Most left from Le Havre. Ships brought bulky good, like tobacco and cotton, eastward to Europe and returned to America with a cargo of steerage immigrants. Shipping advertisements for fares to America were common all over Europe.

Most Germans are said to have traveled in family groups. However, that was not the case of most of the families I have been researching. Henry Blanck was single when he immigrated. Henry Blanck married Melosine Erxmeyer who was also single (or perhaps widowed) when she immigrated. Peter Goehle from the Herrnsheim near Worms in the Rhineland arrive alone in New York in 1873 via Liverpool. Catherine Furst, the mother of Peter's second wife, was born in Auschaffenberg and immigrated either with her brother, Ludwig, or around the same time. The Erxmeyer brothers and Henry Blanck immigrated to the States in the early 1870s by deserting from the German Merchant Marines. This was, in fact, extremely common. Fredrich Erxmeyer's mother, sisters, and wife came on separate ships but within a short span of time. Johann Berend Petermann, born in Ganderkesee, Hanover, married Sophia Steuer in Germany and immigrated either with his wife and small son or around the same time. I have not found their immigration record. Most immigrants had never been farther from their homes than the nearest market town before they set out for America. Here again there are diversions from the norm. The Erxmeyer family lived in several areas in Germany before coming to the States. The Erxmeyer brother, Friedrich and Hienrich, Johann Berend Petermann and Henry Blanck made several voyages to the United States with the German merchant marines. Berend Petermann made at least 13 voyages as a merchant marine and sailed to many exotic ports between 1859 and 1873.

|

|

|

| Collection of Maggie Land Blanck Der Zug der Galzburger durch Deutchland [The migration of Galzburger across Germany] 1732

| |

|

|

| Collection of Maggie Land Blanck

| |

| Song of the Emigrant

Goethe

| |

Collection of Maggie Land Blanck Collection of Maggie Land Blanck Nowel in Germany: FAREWELL TO FATHERLAND - EMIGRANTS EMBARKING FOR AMERICA Every Saturday November 3, 1871 | |

|

|

| Collection of Maggie Land Blanck GERMAN EMIGRANTS EMBARKING FOR AMERICA | |

|

The Voyage Before 1850, the sailing ships on which immigrants came to America took anywhere from ten to twenty four weeks to arrive in America. Later ships, still under sail, but fitted with paddle wheels and steam engines took about six weeks. Conditions were frightful. Immigrant ships were recognized by the smell. After the introduction of the steamships the length of a voyage from Bremen to New York took about seventeen days. Government supervision of sanitation regulations improved the sanitation conditions.

The major ports of embarkation in Germany were Bremen (Bremerhaven) and Hanover. However, many immigrants crossed to English or French ports to leave for America. See Immigration now or at the bottom of the page.

Settlement in the United States Most German immigrants to the United States settled in rural areas. However, between 1860 and 1890 about two-fifth of the German born population lived in cities of twenty-five thousand or more. This is a considerably higher rate than that for native born Americans. Whatever the city, Germans tended to settle in ethnic enclaves, like Kleindeutchland in New York and the German neighborhoods in Hoboken, New Jersey. The largest German community in New York City was from Bavaria. By 1875 German-Americans made up 75 % of New York City's population. Those who settled in New York City were mostly single men and women. Those who were intending to settle elsewhere in the country frequently came in family groups. Most German immigrants married and socialized with people from their own area of origin. They tended to settle by national group. Bavarian clustered together with other Bavarians, and so forth. They rarely married people from other areas of Germany. Occupations were also regionalized. For instance most grocers in the New York area came from Hanover or Hamburg. The Church was an important part of the German immigrant life. Many German immigrants were Lutherans. At the peak of German immigration in the 1880's about one half of all German immigrants were Roman Catholic. Many German churches ran German speaking parochial schools. In 1870 37% of Germans in America worked at skilled trades. Germans were prominent as butchers and tailors, among other trades. German Americans were great socializes. They liked to take the whole family to the beer gardens on Sundays. This caused some friction with there neighbors who frowned on drinking and socializing on the Sabbath. The German immigrant was known to be hard working and hard drinking. In the 1840s there was a lot of anti foreign sentiment much of it directed towards German and Irish immigrants.

Kleindeutchland Most Germans who stayed in New York City settled in Kleindeutchland and the Lindemanns, Fursts, and Goehles were no exception. Kleindeutchland was a primarily German section of New York City that included the 10th, 11th, 13th and 17th ward, that is: from the Bowery to the East River and from 14th Street to Division Street. It included all of the Lower East Side. This area had everything catering to the German speaking population. Residence of Kleindeutchland bought food and clothing in German stores where the signs were in German Gothic letters. They listened to German music; in the beer halls, in band shell in the park, and in German concert halls. They joined German coral groups. They visited German doctors, went to the German theater, read newspapers in German, did their banking in a German bank. The Germans were great joiners, they joined shooting clubs, churches, and lodges. There were German sports teams. Among the favorite sports were soccer and gymnastics. There were German schools and churches. There were "volkfests" which gave people a chance to talk in their local dialect and exchange news from Germany. The majority of German immigrants were skilled workers or small businessmen. They worked in the garment industry, wood working, furniture making, cigar making, printing, shoe making, as musicians, in the food trades (cooks, bakers, brewers, butchers, grocers, saloon owners, barmaids, waiters and waitresses). In the 1880s 50 percent of bakers, 40 percent of butchers and 80 percent of brewers were German. Butchers worked not only in shops, but in slaughter houses and meat packing plants. This work was resembled factory work and not the skilled labor of a butcher shop. Garment work included: tailors, seamstresses, piece workers, millinery, artificial flower making, embroidering, button hole making, cloth cutters. These tasks were often performed at home but there were numerous garment makers lofts and tailor shops. In the 1880s cigar makers comprised owners of large factories, master craftsmen with a handful of journeymen, and slum landlords who's tenants produced cheap cigars in their apartment under sweatshop conditions. In addition, there were larger factories, like iron works, timber and coal yards, furniture factories. Poorer immigrants lived in the southern end of the area while the better off lived in the northwestern part. Buildings were usually 25 feet wide and 4 to 5 stories high and 4 apartments on each floor. Each apartment had about 200 square feet. Later buildings were twice as wide and 7 to eight stories high, housing up to 48 families. Living on one floor of a converted one-family house was desirable. Most families moved frequently for a variety of reasons. Many families worked out of their apartments, cigar makers, piece workers in the garment industry. In order to make ends meet it was common to send children to work or to use the to help with the piece work at home. This happened the world over at this period of time.

Avenue B in New York City was known as the "German Broadway". It was the main commercial street in the area. It was lined with beer halls, oyster bars, and grocery stores. Atlantic Gardens on the Bowery was a great hall lined with bars and lunch counters where people went to drink beer. Entire families frequented the "Biergarden", where there was polka music and accordion playing. Tompkin's square was more or less the geographic center of Kleindeutchland . It was also the endpoint point for the traditional Sunday afternoon stroll. On January 31,1874 it was the site of a riot. About 6,000 workers and their families who had taken to the streets to seek public relief from the unemployment and hunger caused by an economic depression were set on by mounted police with Billy clubs. Kleindeutchland remained primarily a German speaking area of the city until around 1904 when a tragic accident occurred on June 15, 1904. An excursion boat, named the General Slocum, carrying about thirteen hundred people, mostly women and children, on an outing from St. Mark's Lutheran Church on 6th Street east of Second Avenue, caught fire. The life preservers and hoses were rotted and the wind was very strong. The fire burned out of control. Most of the crew and passengers were burned to death or drowned. Kleindeutchland never recovered. It is said that many of the grief stricken German community moved away, many to Yorkville on the Upper East Side. However, a movement out of the Lower East Side was already under awy. German Americans started moving to Yorkville in the 1870 and 1880s. Yorkville extended from 79th Street to 86th Street and from Lexington Ave to the East River. Yorkville boasted newer apartments which were somewhat larger and more comfortable then in the Lower East Side. There were better living conditions but the rents were higher and there was less work close by. Yorkville really only grew with the advent of public transportation in early 1900s. For more information on and images of Kleindeuchland go to Kleindeuchland now or at the bottom of the page. Rebecca Kirschman has graciously shared her research on the General Slocum disaster. Go to The Burning of the General Slocum now or at the bottom of the page.

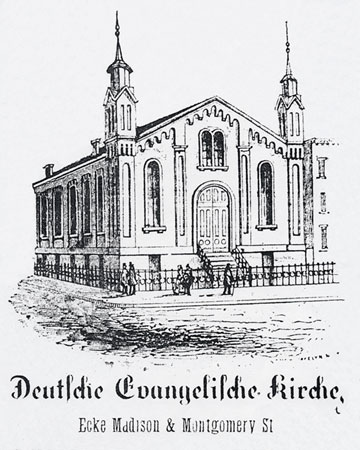

Some German Congregations in Kleindeutchland St. Nicholas Kirche (1833) was the first German Catholic Church in the City. Isabelle Walsh and Frank Goehle were married in St. Nicholas. German Reformed Churches at 129 Norfolk Street and Avenue B at 5th. St. Mark's Lutheran Church at 6th Street and Second Avenue Rivington German Presbyterian Church on Rivington Street. Most Germans in Germany were either Lutheran or Catholic. The US offered more options and there was a wide variety of denominations with German speaking congregations particularly in the large cities. |

|

The Second German Evangelical Reformed Church Madison and Montgomery Streets Peter Goehle and Catherine Christ were married in this church in 1875. Catherine Lindeman, the younger, and Charles BeyerKohler were married in this church in 1888. The church is no longer standing. |

First German Presbyterian Church 292 Madison corner of Montgomery Rev. B Krusi 276 Madison. (1885 & 1888, Directory of Social and Health Agencies of New York City) 1870: The Rev. Bartholomew "Kruesi" was the pastor of the Madison-st. German Presbyterian Church (New York Times) Reverend Bartholomew Krusi (1838-1893) was Swiss-born pastor of the German Presbyterian Church in New York City.

1888: And, on motion of Vice-President Divver, the Presiby Alderman Dowling Resolved, That permission be and the same is hereby given to the German Presbyterian Church, corner Madison and Montgomery streets, to place transparencies on street-lamps, one corner Ridge and Grand streets, one corner Montgomery street and East Broadway and one corner Madison and Montgomery streets, from November 22, 1887, to November 27, 1887, for the purpose of advertising a fair in the above-named church. (Proceedings of the Board of Aldermen, Volume 1888)1903: Mrs. Louise Margaret Krusi, for nine years a worker in charity as an employee of the New York Charity Organization Society, and later, jointly, of the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor, died on January Io as a result of a paralytic stroke. The deceased was the widow of the late Rev. Bartholomew KrŸsi, pastor of the German Presbyterian Church, Madison and Montgomery streets. Her post was in the Joint Application Bureau on the first floor of the United Charities Building, and she did not finally relinquish it until December 2 last, when her speech failed. Mrs. Krusi was president of the Frauenverein and one of the charter members of the Monday Club." The Survey, Volume 10Bartholomew Krusi, pastor of the German Presbyterian Church, Madison and Montgomery streets. |

|

Brooklyn The Atlantic Docks, Brooklyn's biggest 19th century commercial development, comprised over forty acres of protected basin. There were huge grain elevators and warehouses. Access for goods and people from the end of Hamilton Ave to lower Manhattan on the New Ferry was a 12 to 15 minutes trip. The area was active from the mid-1800 until well after the turn of the century. The Germans arrived in Brooklyn the mid 1800s. The highest concentrations of Germans in Brooklyn were in Williamsburg, Bushwick, Greenpoint and Red Hook.

Hoboken Hoboken was another major shipping center in the New York area. Hoboken had Irish, Italian and German enclaves, however, it was the German culture that completely dominated from the 1840's to the start of World War I. (WWI started in Europe in 1914. The US entered the war on April 6, 1917.) Hoboken was known for it's river walks, German parks, news papers, social clubs, and beer gardens. A combination of affordable housing for workers and elegant housing for the well-to-do who liked the views of the New York skyline made it a pleasant place to live. Thousands of people came over by ferry from Manhattan each weekend to enjoy the recreational pleasures of Hoboken. Hoboken underwent a great period of growth between 1880 and 1920 that corresponds to the general period of urban growth in the United States. The number of manufacturing industries in Hoboken increased from 121 in 1879 to 399 in 1899. Most of the concerns were small, with most firms employing less than 20 people. Of the German firms of note was Keuffel and Esser, a manufacturer of surveying instruments. Tom's father, John Blanck, worked for Keuffel and Esser for many years. The Hamburg-American steamship line was established in Hoboken in 1863. In the late 19th century Hoboken had one of the most thriving wharfs in the New York Harbor. It was the New York port for the North German Lloyd Line, the Hamburg American line, the Scandinavian-American line, the Wilson line and the Tietjen and Lang dry-docks. Importing and exporting made Hoboken an important warehousing and wholesaling center. Hoboken was the terminal for the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroads and the Hoboken Shore Railroad. It was also an important point of embarkation for arriving immigrants. The Hoboken Piers of the North German Lloyd Steamship Company and the Hamburg-American Line burned in a huge fire on June 30, 1900. After the fire the two steamship companies temporarily used piers in Brooklyn. By November 1900 both companies had decided to rebuild new steel piers in Hoboken. By April 1901 enough of the piers were in place for the North German Lloyd steamship, Grosser Kurfuerst, to dock in Hoboken. The arrival of Grosser Kurfuerst was greeted with great fanfare. For more information on the fire see The Hoboken Fire now or at the bottom of the page. According to Hoboken History, the Magazine of the Hoboken Historical Museum, issue no. 23, 1999, "The German liner piers, shared by what were then two of the world's biggest and busiest shipowners, the Hamburg-American Line and the North German Lloyd, were built just after the turn of the century. Slender "finger" piers, which extended more than 900 feet out into the Hudson, they were built on the site of the ruins of the previous docks, which were destroyed in the devastating Hoboken Pier Fire of 1900. · After a string of ruinous fires over the years(including 1944), the last of these docks served the American Export Lines until 1870, then collapsed in 1993 and was finally demolished in 1997."The same issue has these comments about the Lackawanna Train Terminal, "Lackawanna Terminal was the largest railway terminal along the banks of the Hudson and was also though to be the very best of its kind. The structure itself is actually the fifth station built on the same site. The current version, which opened in February 1907, was a grand successor to the four earlier stations, all of which burned down. It was linked to Manhattan by ferryboats and, after, 1908, by tunnels under the river. The 225-foot tower, which rose form the center of the terminal, was pulled down in 1948."For more information on Hoboken go to Hoboken now or at the bottom of the page. German Customs in America Germans brought with them the traditions of the old country. Fasching was the German celebration of the period before lent. Sommernachfests was a beer celebration just before Easter. Whit Monday was celebrated with parades and picnics. Everyone participated, from old grandmothers to toddlers. There was lots of beer to drink and worst to eat. Oompah bands and accordions provided music. There was singing, dancing and feasting. Perhaps the biggest German contributions to American culture were Santa Claus and the Christmas tree.

Among our German citizens, the German Christmas customs survive unchanged. Perhaps most of them have become national with us. The Catholic Santa Claus, with his servant Ruprecht, who punishes bad boys, come to distribute nuts and candies on December 6th- St. Nicholas's Day. Christmas, is the festival of the Christ Child, and days before, the house is made clean for His coming. The day is, above all, a family one, and it is spent quietly at home. The presents to the children are distributed early in the morning, and usually are characterized by thrift and usefulness. The larger children often have to wait until Christmas to replace out grown clothes, shoes, and mittens. A gift like a pair of skates is sometimes added, but practical utility is the end kept constantly in view. potato dumplings. A plain cinnamon cake, with ginger-spiced deer and lions crusted with icing and blue and red sugar, and the little round Pfeffernüsse are the festive additions to the board.The Christmas tree was introduced to England when Prince Albert of Germany married Queen Victoria.

|

Collection of Maggie Land Blanck Collection of Maggie Land Blanck Nowel in Germany: Buying Christmas Trees in Berlin

| |

|

|

| Collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

|

| Collection of Maggie Land Blanck A Happy Christmas

| |

|

|

| Collection of Maggie Land Blanck Weihnachsfest der Deutchen Division am Potomac [Christmas with the German Division of the Potomac] German/Americans were the largest ethnic group to fight on the Union side in the American Civil War. Over 216,000 native born Germans fought for the Union. Some regiments were entirely German and German/American. The government recruited right outside Castle Gardens, enlisting the Irish and German immigrants as they got off the boat. Many German immigrants were professional soldiers who had fought in wars in Europe. There is an interesting image from September 1864 at Kleindeuchland depicting the recruiting of the immigrants outside of Castle Gardens. Also see Immigration now or at the bottom of the page.

| |

|

Thanksgiving

It was hard for any immigrant ethnic group to resist Thanksgiving with turkey and cranberries. The German Americans were no exception. They got right into it and by 1890 were having balls, singing fests and gymnastic exhibitions on Thanksgiving eve and night.

| |

|

The German American Community and World War I

The 1910 United States Census indicated that there were 8,282,618 Americans who had been born in Germany or had one or both parents born in Germany. There was a fair amount of Anti-German sentiment in the United States. Most Germans leaned over backwards to show their support of the United States, including changing the spellings of their names to seem less German. Suspicion of German Americans was high during both WWI and WWI but waned when the wars ended. Many German Americans enlisted in both wars.

A Little Bit about Life in Germany From 1648 to 1806 the people derived their legal status from the "corporation" to which they belonged: nobility, clergy, merchants and craftsmen's guilds, university, and the peasantry. Medieval clothing ordinances, laying down what fabrics different social groups might wear, continued to appear well into the eighteenth century. Many Germans lived close to the castle or palace of the nobility and severed them as servants, tenant farmers, stewards, and in various capacities in the courts. The village of Herrnsheim (the birth place of Peter Goehle) was a seat of the ancient noble von Dahlberg family. Aschaffenburg (the birthplace of Catherine Furst) was the the seat of the powerful Archbishop of Mainz. Adolph Erxmeyer was a steward on the Haxthausen estates in Bokendorf. Other German Americans came from the sea port towns of the north. Berend Petermann was a merchant marine from Ganderkesee. Henry Blanck was born in Lehe a suburb of the major German port of Bermerhaven. The Thirty Years' War, a religious conflict between Catholics and Protestants, started in 1618. By the end of the conflict Germany's population was reduced by about 40 percent in the countryside and 33 per cent in the towns. Plague and crowd diseases, such as smallpox and typhus, were big killers during the Thirty Years' War. More people died from disease than from fighting. However, Germany's population grew rapidly in the seventeenth century, despite epidemics, which became common all over Europe from about 1560. Although mortality rates were high, fertility rates were higher. The years following the Thirty Years' War saw a decline in the growth of towns. Territorial rulers interfered with commercial life, erecting toll barriers along roads and rivers and levied excise taxes on goods coming in and out of towns. Poor communication by road and water and a multiplicity of currencies kept regions apart and fostered a parochial outlook. The majority of German towns during the period 1648-1815 either came under the rule of a local prince or sank to the status of small country town. Local rulers crushed traditional town liberties that had been the source of enterprise and commerce. People lived close together in dark houses. Muddy thoroughfares of German towns remained proverbial well into the nineteenth century. Water for washing was obtained from pumps. Water for drinking was obtained from water carts. Night waste was put in buckets to be collected by the "night women" and emptied in the nearest river or gutter. Pigs in the streets were common. A Burgher was a citizen of a town. It was a privileged status compared to the mass of the population. Traditionally the burgher had the duty and right to bear arms and even until the eighteenth century was allowed to carry a dagger. If a burgher moved to another town he had to purchase citizenship usually for cash or by marriage or a mixture of both. The artisan craftsman in the late seventeenth and above all in the eighteenth century was virtually identifiable with the notion of burgher. The guild system continued to exist far longer in Germany than in any other comparable European country. The guild influence in Germany from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century was a staunchly conservative one, affecting not only attitudes and social behavior, but traditional methods of production and distribution. The master craftsmen put obstacles in the way of competitors and opposed initiative in order to retain their privileges. They were successful in defending their right to exercise jurisdiction over their members throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, against both the Emperor and princes. In 1800 guild members constituted some 14-15 per cent of the population of Prussia but only a few paid income or property tax. A trade generally insured at least a minimal income and relative freedom. Craftsmen were addressed as Ehrsam und Namhaft and Ehrbar und Wohlgeacht. Ehrsam and Ehrbar both mean honorable. Namhaft means well-known. Wohl means well or good. I could not find find geacht. However, in January 2011 Jan Kockrow wrote: Explanation: 'geacht' is a very old and nowadays uncommon form of the adjective 'geachtet'. Same applies for 'wohlgeacht', which stands for 'wohl geachtet'. 'geachtet' means 'respected' in English, 'wohl geachtet' could be translated as 'well-respected'. A craftsman's 'honour', expressed in the above forms of address implied many things based on a series of rights and duties in the community. It meant maintaining professional skill, a devout and moral character, and a sense of responsibility to the profession and its dependents and to the community in general. Members of a guild were expected to sit up all night with a sick comrade, and to attend the funeral of a deceased guild member , ensuing that all was done properly to make Eine schone Leiche (a fine corpse). A master craftsman was expected to marry but not before he was qualified. He could not choose just anyone to be his bride. His wife had to come from the same social sphere as he did. In fact, many craftsmen married the daughters or widows of the master whom they hade served as apprentices. In eighteenth century Dulach in south Germany (for which detailed statistical evidence exists) an average of 25 percent of artisan marriages were with such widows, often women twenty or thirty years older. The reasons were obviously financial. The increasing interest in education in the eighteenth century had a profound long-term effect on the craftsman class. In artisan homes in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries reading and owning books were common in Germany. As a class the artisans resisted industrialization as long as they could, not because they would suffer financially by going into the factories, but because to do so would rob them of their "honour" as an "estate" which was bound up with their identity as persons. The first half of the nineteenth century brought profound changes to the artisans and small traders as a group. According to Marx in the Communist Manifesto published in 1848, "Those who, up to now were members of the middle estates, the small industrialists, merchants and rentiers, the artisans and farmers were sinking into the proletariat." An ever increasing number of skilled artisans were failing to establish themselves as masters and there was a general widespread decline in the property owing classes in the 1840s. A working man's household circa 1850 (with the average laborer's wage of 100-150 taler) would have only about on fifth of the income of a comfortable bourgeois family, but would be regarded as having a standard far above that of the poor. An apprentice for a craft could serve up to five years with a master or three and a half if his parents could afford to pay debentures or the boy was well known in the community. The apprentice worked long hours, from five or six in the morning until seven or eight at night. Often he was not working on the craft he had apprenticed for but was running errands or doing drudge work for the household. There was an attempt at revolution in the autumn of 1848 and the spring of 1849. Support for the revolution came from craftsmen and small traders (who were suffering from both material want and a loss of status), from the educated (with few prospects of employment), and from middle and lower ranking classes (dissatisfied with their condition). The most political minded were the wandering artisans, who came into contact with radical groups in France, Switzerland and Germany who were concerned with improving the conditions of the lower classes and organizing a working class movement. The German artisans, however, were more interested in national or religious questions than in labour movements. Communist literature was hardly know to them. The first waves of the industrial revolution in Germany occured 1850 to 1873. For images and more information on life in Germany go to Life in Germany now or at the bottom of the page.

My family includes the following immigrants from Germany:

For more information on Julius, Catherine and Peter, et all go to Goehle Introduction now or at the bottom of the page.

All of the occupations for the German American ancestors (with the exception of Fredrick Kettler) fall under the category in Germany of artisan and craftsman.

|

|

|

| Goehle Introduction |

| Blanck Introduction |

| Petermanns |

| Images of Life in Germany |

| Immigration |

| New York City Information and Images |

| Kleindeutschland and the Lower East Side of New York |

| 88 Sheriff Street, the Lower East Side |

| Tenements |

| The Burning of the General Slocum |

| The Hoboken Fire |

| Hoboken Images |

| If you have any suggestions, corrections, information, copies of documents, or photos that you would like to share with this page, please contact me at maggie@maggieblanck.com |

|

RETURN TO TOP OF PAGE |

| Please feel free to link to this web page. You may use images on this web page provided that you give proper acknowledgement to this web page and include the same acknowledgments that I have made to the provenance of the image. Please be judicious. Please don't use all the images. You may quote from this web page and use any cited quotes on this web page provided you give proper acknowledgement to this web page and include the same acknowledgments that I have made to the provenance of the information. Please do not cut and paste the whole page. You may NOT make use any of the images or information on this web page for your personal profit. You may NOT claim any content of this web page as your original idea. Thanks, Maggie |

| ©Maggie Land Blanck - Page created 2005 - Latest update, June 2016 |